Last night, current Affairs program Four Corners had a look of the risks to families in the age of Big Data.

Earlier in the day I had the opportunity to speak on ABC 702 Sydney with the program’s reporter, Geoff Thompson, to discuss some of the issues and take listeners’ calls about Big Data and security.

What stood out from the audience’s comments is how most people don’t understand the extent of how data is being shared. The frightening thing is the Four Corners program itself understated the extent of how information is being distributed around the internet.

Looking beyond social media

Social media sites like Facebook are an obvious and legitimate area of concern with most people not understanding the ramifications of the terms and conditions of these services, however Big Data is a far more that what you share on LinkedIn or Instagram.

A major point of the program was how the New South Wales police force’s Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) equipment stores photographs of car license plates.

One of the applications of ANPR shown during the program was how an officer can be warned that a vehicle has owned by someone potentially dangerous or used in a suspicious situation, allowing them to be more cautious if they decide to pull a car over. Probably the greatest application is getting unregistered, uninsured or unlicensed drivers off the road.

Those sorts of usage is the positive side of Big Data and its role in reducing the road toll, the example also illustrates how data points are coming together with the internet of machines as traffic lights, road signs and cars themselves are communicating with each other and those police databases.

When that information is put together there’s a lot valuable intelligence and that’s why people are concerned that the NSW Police are storing millions of apparently useless images of car number plates with the time and location of the photographs.

These technologies aren’t just being used in shopping centres; instore mobile phone tracking combined with the same numberplate recognition the police use watching who is entering the carparks makes it possible to predict buying patterns and target offers to shoppers.

Couple that information with store loyalty cards and add in rapidly developing facial recognition, retailers have a very powerful way of monitoring how their customers behave.

“What instore analytics does is it takes the same kind of capablities that e-commerce sites have had for more than a decade and apply them to brick and mortar stores,” says Retail Next’s Tim Callen. Using the store’s CCTV system the company applies facial recognition software to track shoppers’ behaviour.

Securing the data feeds

The immediate concern is the security of this data, we’ve covered the hackable baby monitor and the Four Corners program examined Troy Hunt’s exposure of security flaws in Westfield Shopping Centres’ Find My Car App. Similar security concerns surround government databases like the NSW Police’s numberplate store.

As we’ve seen with the repeated data breaches of 2011, the management of big and small organisations like Sony or Stratfor don’t take security seriously. It’s hard to recall any senior public servant being held accountable for a security breach by their department.

A billion points of data

On their own, each of these data points means little but for a motivated marketer, tenacious police officer or determined stalker pulling those separate information sources together can pull together an accurate picture of a person’s private information, habits and beliefs.

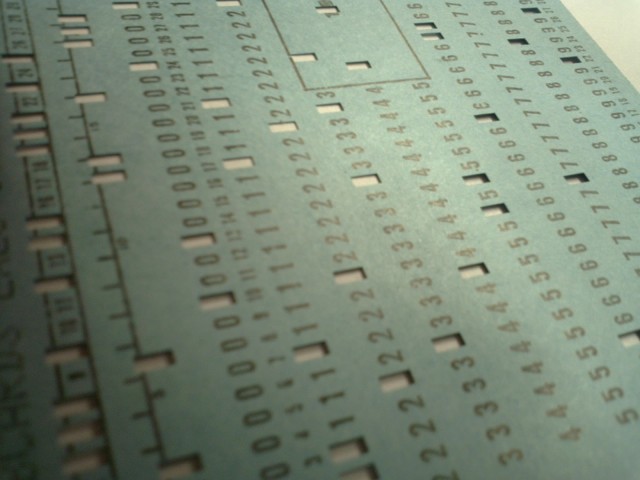

Almost all the collectors of this data claim this information is anonymised or isn’t personal information, unfortunately there’s mismatch between the definition of private data and reality as number plates and mobile phone MAC addresses are not considered private, however they provide enough insight for an individual to be identified.

That aspect isn’t understood by most people, the final caller to the ABC Radio spot asked why she should be bothered worrying about privacy – it doesn’t matter.

As French politician Cardinal Richelau said in the Seventeenth Century, If you give me six lines written by the hand of the most honest of men, I will find something in them which will hang him

Today we each have six million points of data that can hang us, in a decade it could easily be a billion. We need to understand and manage the risks this presents while enjoying the benefits.

Similar posts: