Last week my wife bought a new coffee maker, an impressive, all singing and dancing device that’s a vast improvement on the decade old machine it replaces.

Despite drinking three or four cups of coffee a day, for three days after the new machine arrived I didn’t make one long black or cappuccino. The reason was I didn’t have time to figure out how to use it or the high tech coffee grinder that it came it.

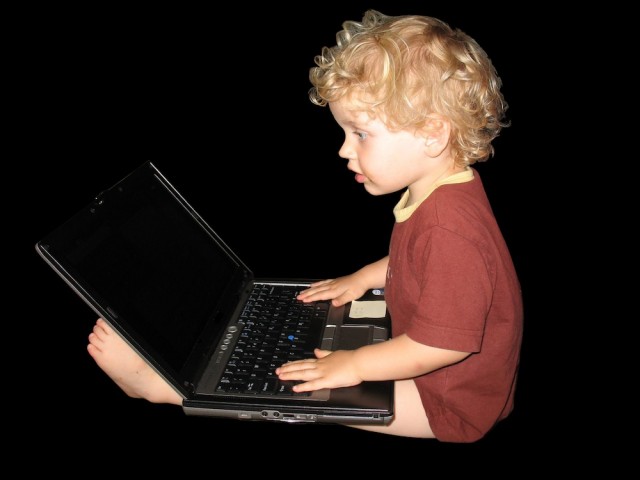

Being time poor is one of the greatest barriers in adopting new technologies as business owners, managers and staff often don’t have the time to learn another way of doing things.

The coffee machine reminded me of something I learned with a business I was involved in the early 2000s. We were trying to sell Linux systems into small and medium businesses.

We had some success selling into small service businesses like real estate agents and event managers where the owners could see the benefits of open source software and, in many cases, had a deep suspicion or resentment towards Microsoft’s almost monopoly on small business software.

Despite the success in selling the systems, the business though came undone because many of the clients’ staff members refused to use the Linux machines, as one lady put it to our frustrated tech “I want to click on the Big Blue W when I want to type a letter.”

That Big Blue W was Microsoft Word and no amount of cajoling could convince the lady to use any of the open source alternatives — she knew what worked in Word and she had neither the time or inclination to learn any thing different.

Eventually that customer gave up trying to convince their staff to use non-Microsoft systems and the computers were reformatted with Windows, Office and all the other standard small business applications installed.

This happened at almost every customer’s office and eventually the business folded.

For those of us involved in the business the lesson was clear, that time poor users who are content with their existing way of working need a compelling reason to switch to a new service.

In many ways this is the problem for legacy businesses — the sunk costs of software are more than just the purchase price, there’s the time and effort in migrating away from existing products and training staff.

When we’re selling new technologies, be it cloud computing services, linux desktops or fancy new coffee machines, we have to understand those costs and the fears of users or customers who’ve become accustomed to an established way of doing things.

In the eyes of many workers new ways of doing business are scary, challenging and often turn out to be more complex and expensive than the salesperson promised. In an age where marketers tend to over promise, that’s an understandable view.

For those selling the new products, the key is to make them as easy to use and migrate across to. The less friction when making a change means the easier it is to adopt a new technology.