The San Francisco Chronicle has a great feature mapping apartment rental service AirBnB’s effects on the city’s economy.

By trawling through the AirBnB database, The Chronicle found 4,800 properties for rent in the city to glean a great deal of information that the company is not keen to share.

A key point from the survey is that over 80% – 3200 – of the properties are householders renting out spare rooms or their places while they are away, which is exactly what AirBnB claim their service is designed for.

The other, professional hosts are what’s attracted the wrath of regulators in cities like New York, where it appears unofficial hotels are skating around taxation and safety regulations.

A new breed of middleman

Catering for these professional hosts has seen another group of middlemen service pop up and The Chronicle features Airenvy, a service that helps landlords manage their properties.

Airenvy is now the biggest San Francisco host, managing 59 properties on behalf of its clients and charging 12 percent commission for dealing with the daily hassle of looking after guests. Since launching in January it employs twelve staff.

Unlike many of the internet middlemen, Airenvy does seem to add value to the renting process above being a simple listing service. For absentee hosts, the fees would seem to be worthwhile in reducing risks and problems.

Filling the gaps

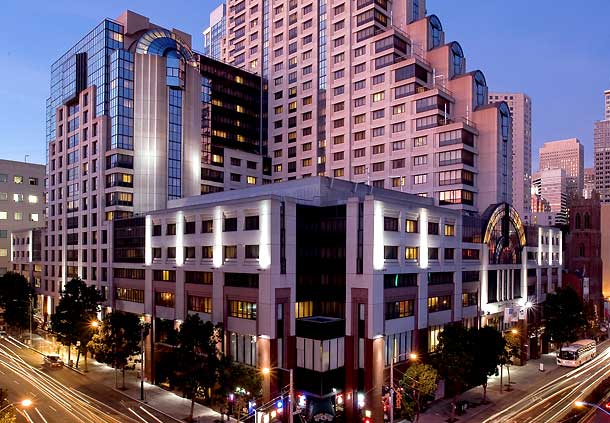

A unique thing about San Francisco is the concentration of hotels around Union Square with 20,000 of the city’s hotel rooms within a ten minute walk of the Moscone Centre.

For non-convention visitors, particularly those visiting family or friends, AirBnB is an opportunity to get a place out of downtown.

The price ranges reflect the service’s diversity as well; from $18 a night for a couch through to $6,000 for a mansion. The average though is close to a typical hotel rate of $226 a day.

The effects of AirBnB

What the survey shows is AirBnB has diversified San Francisco’s accommodation options without the problems being encountered in New York.

That isn’t to say there aren’t problems – the Silicon Valley model of pushing responsibility and consequences onto users leaves a lot of risk for the both the service and its customers – however AirBnB is another example of how industries are evolving as information becomes easier to find.

Another thing this survey shows is the new breed of data journalism and how analysing the numbers can be the foundation of building great stories.

The AirBnB and the changing global travel industry is a great story in itself as the San Francisco Chronicle has shown.