Both Microsoft and Google yesterday reported their second quarter earnings for 2013 and both missed the targets expected analysts. Does this really mean anything?

Microsoft’s earnings were particularly notable as they included a $900 million dollar write off on Surface RT inventories, this almost certainly means a key part of the company’s tablet strategy has failed.

What’s striking in Microsoft’s earnings report is the terrible performance of the Windows Division which saw sales increase 10% year-on-year to 4.4 billion dollars, but earnings collapse by over 50%. Excluding the Surface RT write off, the division would still have seen a ten percent fall.

The company’s statement emphasised how the division is struggling with increasing costs.

Windows Division operating income decreased $1.3 billion, primarily due to higher cost of revenue and sales and marketing expenses, offset in part by revenue growth. Cost of revenue increased $1.2 billion primarily reflecting product costs associated with Surface and Windows 8, including the charge for Surface RT inventory adjustments of approximately $900 million. Sales and marketing expenses increased $344 million, reflecting advertising costs associated with Windows 8 and Surface.

At Google, the company’s 2nd Quarter report show trend is still upwards but the core business of online advertising is showing some cracks as the total number of paid clicks grows, but the value of each falls. At the same time traffic aquisition costs are rising at the same rate as revenues.

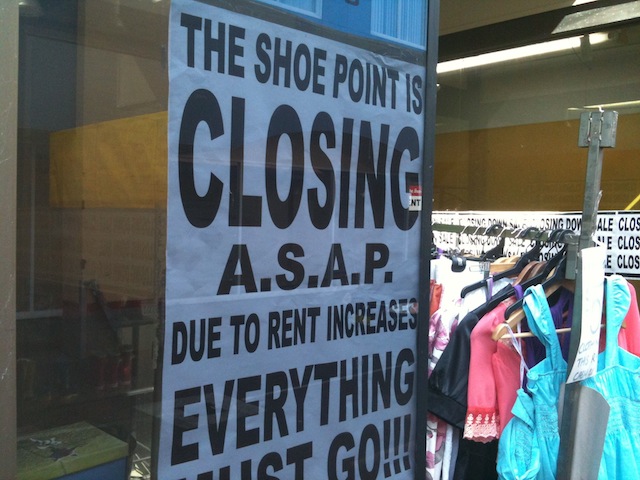

This could indicate that advertisers’ appetite for online links is fading. For smaller businesses, the cost of adwords campaigns has been escalating to the point where the old days of newspaper classifieds and Yellow Pages listings start to look cheap.

Couple the cost of advertising with the inevitable ‘ad blindness’ that web surfers have developed and a worrying trend for Google starts to appear. Overall Google’s net profit margin was 26%, down from 31% a year earlier.

While both companies remain insanely profitable – Google earned $14 billion this quarter and Microsoft $6 billion – both businesses are showing stresses as their markets evolve. It proves no business can afford to be complacent in these times.

That the average age of Australian small business owners is increasing shouldn’t be surprising given

That the average age of Australian small business owners is increasing shouldn’t be surprising given