We learned a lot from the Global Financial crisis.

Radio Rentals tells us “your credit history is history”

We learned a lot from the Global Financial crisis.

Radio Rentals tells us “your credit history is history”

“Nobody got girls on the helpdesk” says Mikkel Svane, founder of online customer service company Zendesk.

Mikkel hopes to make customer service sexy again as businesses find they have to focus on keeping clients happy.

This is a reversal of management thinking of the 1980s where, as Mikkel says, “customer service is a cost centre, outsource it, don’t spend any time on it and don’t let customers steal any of your time.”

Now the internet gives customers to tell the world about a company’s service, the days of outsourcing or disregarding support are over.

Cloud technologies are changing how software is used in business, as Mikkel found when he and his partners started Zendesk.

It became very obvious that building something that was easy to adopt, web based and integrated with email, websites. Something easy to use that didn’t clutter the customer service experience.

Something that moved from managing the customer service experience to focusing on customer service.

We built it, put it out there and customers starting coming.

A lot of these companies thought they could never implement a customer service platform. Suddenly small companies found they could compete with bigger competitors.

Having customers signing up proved to be a big advantage in Silicon Valley, no-one knew anything about a Danish company, but with local customers starting coming on board US Venture Capital firms understood what the company does.

That customer base proved powerful as Zendesk has to date raised $84 million dollars over four rounds of VC funding and is looking at a stock market float with an IPO in the next few years.

“Silicon Valley has a great tradition of building businesses.” Says Mikkel, “coming to Silicon Valley was such a big step for Zendesk, in taking it from being some little startup to being a real company that could scale very quickly.”

Groupon is a good example, when Mikkel and his team first met the Groupon team the group buying service was a team of four guys in Detroit. Groupon founder Andrew Mason personally signed off on the initial Zendesk subscription.

“What the hell is this company, we don’t get it.” Mikkel said at the time.

Three years later Groupon was the fastest growing company in history with thousands of support agents on their systems supporting hundreds of thousands of products.

Despite Groupon’s recent problems, Svane is proud of how Zendesk helped the group buying service with growth that no business had seen before.

“With Zendesk they got not only a beautiful, elegant system they also got the scale and the trajectory. Imagine if they’d tried to do that with an Oracle database? You’d have never been able to grow so quickly.”

In the past we talked about platforms – the Oracle platform, the Microsoft plaftorm – today the Internet is the platform.

“We are a good citizen on the Internet platform,” says Mikkel. “Shopify is a good citizen of the internet platform, these type of tools are easy to integrate. We are all good citizens of the Internet platform.”

Having these open system is the great power of the cloud services, they way they integrate and work together adds value to customers and doesn’t lock them into one company’s way of doing things.

Vendor lock in has been a curse for businesses buying software. The fortunes of companies like Oracle, Microsoft and IBM have been built holding customers captive as the costs of moving to a competitor were too great.

Cloud services like Zendesk, Shopify and Xero turn this business model around which is one of the attractions to customers and it’s why huge amounts of money are moving from legacy solutions to cloud based services.

Another reason for the drift to cloud services is the reduction in complexity, the incumbent software vendors made money from the training and consulting services required to use their products.

Having simple, intuitive systems makes it easier for companies to adopt and use the new breed of cloud services.

Mikkel’s aim is to help businesses focus on their customers and products rather than worry about IT and infrastructure. In the long term it’s about helping organisations establish long term relations with their clients.

“Companies today realise that it doesn’t matter how much it matters how much I can sell to you right now, it pales into in comparison of how much I can sell you over the lifetime of our relationship. This ties into the subscription economy. It’s much more important for companies to nurture the long term lifetime relationship.”

Having a long term relationship with customers is going to be one of the keys for business success in today’s economy.

The days of transaction based businesses making easy profits from skimming a few percent off each sale are over and companies have to work on building long term relationship with customers.

Services like Zendesk, Xero and Salesforce are those helping new, fast growth companies grab these opportunities. For incumbent businesses, it’s not a time to be assuming markets are safe.

I first heard the term “throwing the problem over the fence” from a telco project manager a few years ago, it describes how modern organisations shift risk to others.

Throwing the problem over the fence usually involves contracting out a task, the philosophy is once the contract is signed delivery is no longer management’s problem, it’s now the responsibility of the contractor. Once the job is over the fence it’s out of sight and out of mind.

Governments, financial institutions and most corporations have become very good at throwing their problems over the fence.

A core tenet of 1980s management thinking is contracting out; freeing executives from the tedious task of actually doing their jobs lets them focus on the important things in life, like securing performance bonuses.

Of course you can’t contract out risk – risk is like toothpaste, squeeze it in one place and it oozes out somewhere else.

Unlike toothpaste, risks have a habit of growing if they are ignored. Which becomes a problem for whoever is unwittingly on the other side of the fence.

In “The Crash That Stopped Britain” author Ian Jack looked at the causes of the October 2000 Hatfield train accident which threw the nation’s railway network into chaos.

Jack correctly predicted that no-one would be found responsible as the tangle of rail operators, maintenance companies, financiers, labour hire firms and regulators made it almost impossible to determine exactly where responsibility for a fatal failure lay.

Diffusing responsibility is partly by design although originally the idea was to save costs, the theory being that tendering work previously done in house to the lowest cost provider would save money.

Instead its caused an escalation in costs as contracting out meant an increase in middlemen as financiers, lawyers, project managers, contract administrators – of which I was once one – and many others are drafted in to manage the outsourced contracts.

Throughout the Anglosphere – the US, UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand – the results of embracing this mentality has meant skyrocketing costs and delays in public work projects, a good example being the Southern Sydney Freight Line which was three years late and 250% over budget.

Naturally no-one is held responsible for the delays, cost over-runs or lousy initial planning and estimating on that project, which is a happy result for everyone except the taxpayer who foots the bill.

While the cost of building railways, schools and motorways is a chronic problem, a far more bigger issue is the role of “throwing problems over the fence” in the financial industry.

Securitisation was seen as a magic bullet for the banking industry in the 1990s, the Basel Accords allowed banks to bundle up their entire home loan portfolios and throw them over the fence to fund managers and their unwitting investors.

When the inevitable happened with the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, it was difficult to attribute exactly who held the mortgages, let alone who was responsible for the losses among the mass of brokers, ratings agencies, fund managers and bankers who’d profited so well from the boom.

The only thing we could be sure of was that it was the taxpayer – you, your children and grand-children – who ended up holding the problem when the GFC’s bills were hurled over the last fence.

Risk isn’t something that can be thrown over a fence, eventually it comes back in a bigger and nastier way. The question is who ends up dealing with it.

The genius of political and business leaders in the last 30 years has been in how they’ve thrown their responsibilities over the fence while retaining the perks and privilege of holding responsible positions.

Generally it’s taxpayers and shareholders sitting on the other side of the fence who have to deal with the costs and they aren’t getting cheaper.

One of the core objectives 1980s management philosophy is to shift costs and risks onto others. Staff training is one area that caught the brunt of the drive to slash expenses for short term gain, as a consequence we have a skills crisis with offers opportunities for savvy entrerpreneurs.

In Why Good People Can’t Get Jobs: Chasing After the ‘Purple Squirrel Wharton management professor Peter Cappelli discusses his recent book that looks at this problem.

Cappelli’s argument is that companies aren’t offering enough for the skills they desire, they often ask too much of candidates and they won’t train staff.

In Cappelli’s book, he claims that staff training has plummeted;

One of your chapters in the book is called “A Training Gap, Not a Skills Gap.” You have some figures showing that in 1979, young workers received an average of two and a half weeks of training per year. By 1991, only 17% of young employees reported getting any training during the previous year, and by last year, only 21% said they received training during the previous five years.

The predictable consequence of neglecting training for the last thirty years is we now face skills shortages and those responsible – the managers and business owners who refuse to train workers – are now demanding governments do something about it.

In many ways today’s skills shortages epitomise the short termism of 1980s thinking and how we now find society, and business, is struggling with the long term effects and costs.

Wherever there’s a problem there is opportunity and there’s a breed of businesses, training companies and workers who will be taking advantage of the failures of the previous generation of managers.

For those stuck in the 1980s mindset that training, like most staff expenses, is a cost and not an investment they are going to struggle in a world where adding value is more profitable than being the lowest cost provider.

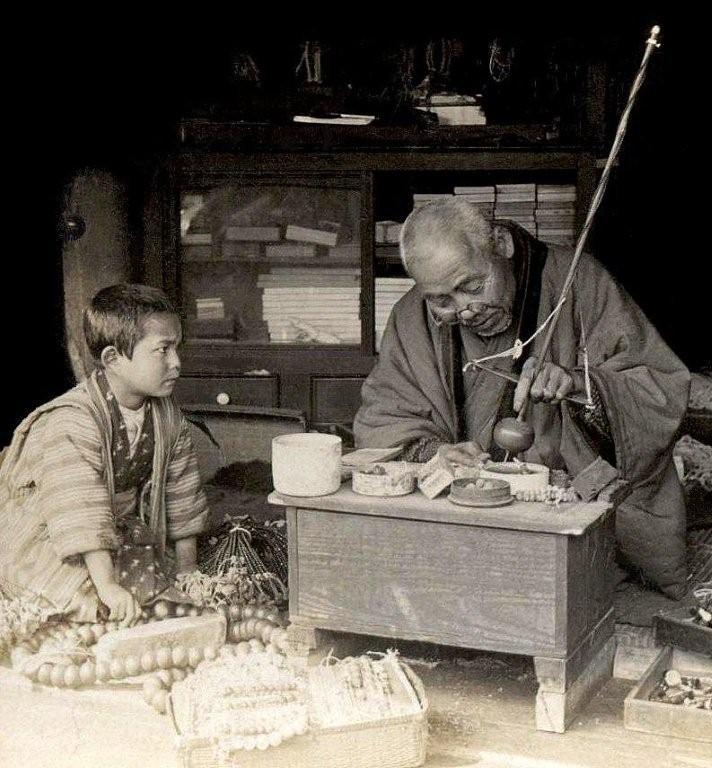

The photo THE BEAD MAKER — Apprentice Watches the Master — A Rosary Shop in Old Meiji-Era Japan was posted to Flickr by Okinawa Soba.

A Telegraph profile of Joanna Shields, the incoming Chief Executive of London’s Tech City Investment Organisation, is an interesting view of how we see economic development and the route to building the industrial centres of the future. Much of that view is distorted by the ideologies of our times.

London’s Tech City is a brave project and somewhat reminiscent of future British Prime Minister Harold Wilson’s 1963 proclamation about the UK’s future lying in harnessing the “white heat of technology.” From Dictionary.com;

“We are redefining and we are restating our socialism in terms of the scientific revolution…. The Britain that is going to be forged in the white heat of this revolution will be no place for restrictive practices or outdated methods on either side of industry.”

Fifty years later a notable part of Wilson’s speech is the use of the word “socialism” – the very thought of a mainstream politician using the “s-word” today and being elected shortly afterwards is unthinkable.

Today the ideology is somewhat different – much of Tech City’s objectives are around aping the models of Ireland and Silicon Valley – which in itself is accepting the failed beliefs of our times.

Based around London’s “Silicon Roundabout” – a term reminding those of us of a certain age of a childhood TV series – the heart of the Tech City strategy lies the tax incentives used by the Irish to build the “Celtic Tiger” of the 1990s and government investment funds to create an entrepreneurial hub similar to Silicon Valley, something also done in Dublin with the Digital Hub.

It’s hard not to think that copying these models is a flawed strategy – Silicon Valley is the result of four generations of technology investment by the United States military which is beyond the resources of the British government, and probably beyond today’s cash strapped US government, while the Celtic Tiger today lies wounded in the rubble of Ireland’s over leveraged economy.

At the core of both Silicon Valley’s startup culture and Ireland’s corporate incentives are the ideologies of the 1980s which celebrates a hairy-chested Ayn Rand type individualism while at the same time perversely relying upon government spending. Ultimately failure is not an option as governments will step in to guarantee investment returns and management bonuses.

Just up the M1 and M6 from London’s Silicon Roundabout are the remains of what were the Silicon Valleys of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The manufacturing industries of the English Midlands or the woollen mills of Yorkshire revolutionised the global societies of their times. These were built by individuals and investors who knew they could be ruined by a poor investment and managers who retired to the parlour with a pistol if the enterprise they were trusted to run failed.

Today’s investment attraction ideologies – tax discounts to big corporations and grants to entrepreneurs – are in a touching way not dissimilar to Harold Wilson’s 1960s belief in socialism.

At the time of Wilson’s 1963 speech China and much of the communist world were showing that socialism, with its failed Five Year Plans and Great Leaps Forward of the 1950s, was not the answer for countries wanting to harness the “white heat of technology.”

Similarly today’s Corporatist model of massive government support of ‘too big to fail’ corporations is just as much a failed ideology, like the socialists of the mid 1960s had their world views had been framed in the depression of the 193os, today’s leaders are blinded by their beliefs that were shaped by the freewheeling 1980s.

Whether the next Silicon Valley will be in London, or somewhere like Nairobi or Tashkent, it probably won’t be born out of a centrally planned government initiative born out of the certainties of Margaret Thatcher or Ronald Reagan anymore than the 1960s technological revolution was born out of Karl Marx or Josef Engels.

Silicon Valley itself was the happy unintended consequence of the Cold War and the Space Race, which we reap the benefits of today.

Every ideology creates its own set of unintended consequences, those created by today’s beliefs will be just as surprising to us as punk rockers were to the aging Harold Wilson.

Maybe Tech City will help Britain will do better at this attempt to regain its position as global economic powerhouse, but you can’t help thinking that economic salvation might come from some West Indian or Sikh kid working out of a storage unit in Warrington than a bunch of white middle class guys celebrating a government grant over a glass of Bolly in Shoreditch.