In a great post, The Wine Rules looks at what ails the Australian wine industry after the news of Cassella Wine’s problems.

Three things jump out of Dudley Brown’s article – how industry bodies are generally ineffectual, the failure of 1980s conglomerate thinking and how fragile your position is when you sell on price.

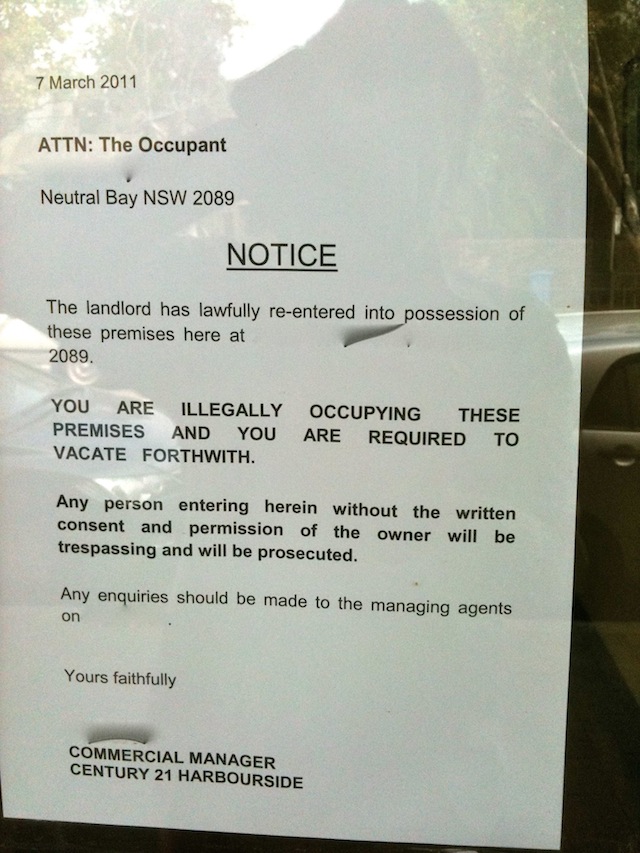

Selling on price

It’s tough being the cheapest supplier, you constantly have to be on guard against lower cost suppliers coming onto the market and you can’t do your best work.

Customers come to you not because you’re good, but because you’re cheap and will switch the moment someone beats you on price.

Worse still, you’re exposed to external shocks like supply interruptions, technological change or currency movement.

The latter is exactly what’s smashed Australia’s commodity wine sector.

A similar thing happened to the Australian movie industry – at fifty US cents to the Aussie dollar filming The Matrix in Sydney was a bargain, at eighty producers competitiveness falls away and at parity filming down under makes no sense at all.

Yet the movie industry persists in the model and still tries to compete in the zero-sum game of producer incentives which is possibly the most egregious example of corporate welfare on the planet.

When you’re a high cost country then you have to sell high value products, something that’s lost on those who see Australia’s future as lying in digging stuff up or chopping it down to sell cheaply in bulk.

Industry associations

“It’s like a Labor party candidate pre-selection convention” says Brown in describing the lack of talent among the leadership of the Australian wine industry. To be fair, it’s little better in Liberal Party.

There’s no surprise there’s an overlap between politics and industry associations, with no shortage of superannuated mediocre MPs supplementing their tragically inadequate lifetime pensions with a well paid job representing some hapless group of business people.

Not that the professional business lobbyists are any better as they pop up on various industry boards and government panels doing little. The only positive thing is these roles keep such folk away from positions where they could destroy shareholder or taxpayer wealth.

Basically, few Australian industry groups are worth spending time on and the wine industry is no exception.

Australia conglomerate theory

One of the conceits of 1980s Australia was the idea that local businesses had to dominate the domestic market in order to compete internationally.

A succession of business leaders took gullible useful idiots like Paul Keating and Graheme Richardson, or the Liberal Party equivalents to lunch at Machiavelli’s or The Flower Drum, stroked their not insubstantial egos over a few bottles of top French wine and came away with a plan to merge entire industries, or unions, into one or two mega-operations.

It ended in tears.

The best example is the brewing industry, where the state based brewers were hoovered up in two massive conglomerates in 1980s. Thirty years later Australia’s brewing industry is almost foreign owned and has failed in every export venture it has attempted.

Fosters Brewing Group was, ironically, one of the companies that managed to screw the Australian wine industry through poorly planned and executed conglomeration. Again every attempt at expanding overseas failed dismally.

In many ways, the Australian wine industry represents the missed opportunities of the country’s lost generation as what should have been one of the nation’s leading sectors – that had a genuine shot at being world leader – became mired in managerialism, corporatism and cronyism.

All isn’t lost for the nation’s vintners or any other Aussie industry, Dudley Brown describes how some individuals are committed to delivering great products to the world. There’s people like them in every sector.

Hopefully we’ll be able to harness those talents and enthusiasm to build the industries, not just in wine, that will drive Australia in the Twenty-First Century.

Picture courtesy of Krappweis on SXC.HU