Chinese manufacturing has been in the news recently with various exposes of factory conditions by the New York Times, the now discredited Mike Daisey and a fascinating look at US store chain Wal-Mart’s supply chain by Mother Jones’ Andy Kroll.

In his examination of Wal-Mart’s Chinese suppliers Andy Kroll interviews factory owners and managers with a common theme, they are all loath to be identified for fear of incurring Wal-Mart’s wrath.

This is wall of silence is familiar in Australia; the reluctance of local suppliers to speak about the conduct of the Coles’ and Woolworths’ policies has hobbled enquiries into the domestic retail market.

Another aspect Chinese and Australian have in common is how the retailers drive down costs with big buyers insist upon regular price reductions from their suppliers.

This is what happens when your business is a price taker that relies on one or two suppliers; you accept what you’re offered or lose a large chunk of your business.

With many of Australia’s industry sectors now dominated by one or two incumbents, this way of doing business is now the norm rather than the exception.

As a nation Australia’s finding itself in that position as well. Now our governments and business leaders have decided Australia will only dig stuff up with a few favoured, uncompetitive industries like car manufacturing being being protected, the entire country is in a position not dissimilar to a Foshan coat hanger manufacturer.

Having that dependency on one or two major customers is a risk and when the commodities boom turns to bust – commodities booms always do – our relationships with these customers will be tested.

When that test comes, the clumsy way the Federal government has banned Chinese companies from tendering to the National Broadband Network or blocked investment in mining projects may turn out to be mistakes.

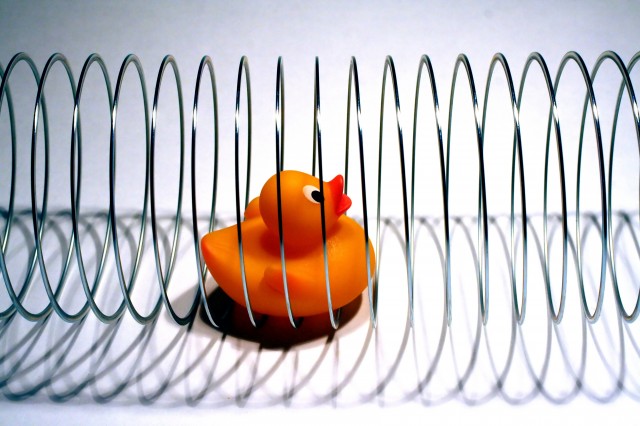

This is the problem with being a price taker selling a commodity product, you become hostage to fortune and when the market turns against you there isn’t a great deal you can do.

In the early 2000s computer manufacturers like Dell and HP decided to sell commodity products then watched with despair as Apple captured the premium, high margin end of the market. Neither business has truly recovered.

Being trapped at the commodity end of a market is not a comfortable place to be, particularly if you don’t have a plan to move up the value chain.

If your business is currently selling low margin, commodity goods then it’s worthwhile considering what Plan B is should the market turn against you. You might also remember to be nice to your customers

At least you’ll show you have more forethought than our leaders in Canberra who seem to like to play with dragons without thinking through the consequences.