Once dominant PC industry duo Microsoft and Intel have had their positions shaken with the rise of cloud computing and smartphones. Can the PC upgrade cycle help them reclaim their fortunes?

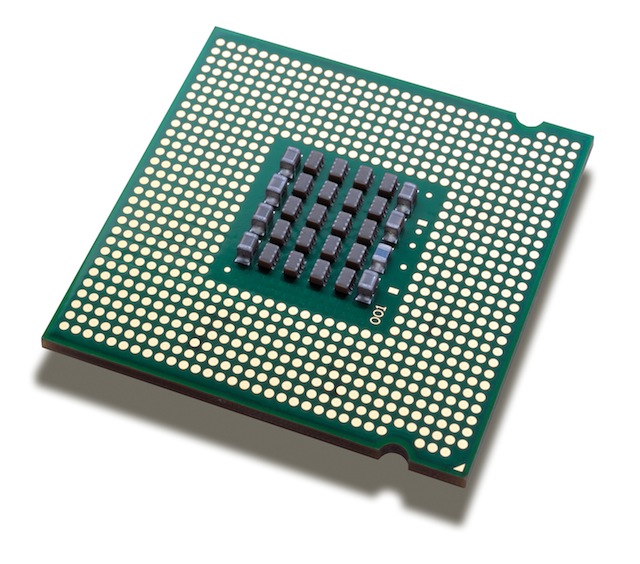

In the early days of the PC industry, chips mattered. Twenty years ago the release of the Intel 486 CPU was big news and careers rose or fell depending on whether an IT manager chose DX-33 or SX-66 chips for the company’s fleet of desktops.

Today few people care enough to get passionate about what’s driving their smartphone or tablet computer.

Intel, who are currently promoting their new range of Central Processing Units, and Microsoft are in an interesting position as their traditional dominance in server, desktop and laptop computers is being challenged by the rise of smartphones and tablet devices.

For most of the 1990s and 2000s the two companies dominated the PC market so completely that the generic term for the sector was ‘Wintel’ – the combination of Windows and Intel.

A core part of the old Wintel business model was the four year upgrade cycle, that most computers would be replaced every three to five years giving Microsoft, Intel and the rest of the IT industry a ready made market for new equipment.

That business model was broken by Microsoft’s disastrous Vista operating system and never recovered as non Wintel portable devices and cloud computing services took away the need to upgrade a server, desktop or laptop computer every four years.

For Intel, matters weren’t helped by their powerful but energy hungry chips not being suitable for tablet computers and smartphones which further eroded their sales as the market moved to portable devices.

Despite those changes to the marketplace, Intel continue to focus on that four year cycle, at their media lunch in Sydney yesterday they emphasised the costs of running older technology.

They do have a point with their claims that servers older than four years deliver four percent of the computing power but consume 65% of the energy, making those antiquated systems far less efficient than newer equipment.

Unfortunately for Intel many businesses will be looking at outsourcing their servers to the cloud when the next technology refresh comes along, so the energy and efficiency arguments are a different matter.

On the desktop, things are somewhat different as most workers still prefer to work at a PC and Intel do have a case for upgrading both business and home systems.

Probably the biggest opportunity will be Microsoft’s pending retirement of Windows XP which will see a wave of business and home users who’ve been content with decade old computers looking at moving off systems that are no longer supported.

Another feature going for Intel and Microsoft are newer computer technologies such as touchscreens and Intel’s own wireless display technology, branded as Wi-Di, which older systems can’t support.

Whether this is enough to entice technology addled consumers and businesses across to new systems remains to be seen, but it’s a challenge for both Microsoft and Intel to reclaim their once dominant market positions.