Technologies like the internet of things, cloud computing, 3D printing and big data are changing our industries and society. At the ACI Connect event today, I gave a presentation on some of the opportunities, risks and ethical issues facing technologists and engineers in the connected economy.

While many of the engineering principles underlying these technologies aren’t new, their scale and the power they give businesses and governments means there are serious ethical, security and societal issues we have to consider.

This presentation explores some of those issues and the technologies and trends driving them.

Entering the Data era

A conceit among technologists is that we’re in an unprecedented era of change. This is not true.

The Twentieth Century saw massive restructuring of our society as the telephone, mains electricity, the motor car and television changed our society. Many of today’s settled industries came out of the huge technological steps forward over the last hundred years.

Just as cheap energy – delivered to us through the motor car and mains electricity – defined the Twentieth Century, this century will be defined by easily accessible and abundant information.

Those changes over the last hundred years give us some hint as to where we are going; the shifts that saw coal carters, newspaper sellers and night soil men eventually become extinct, along with a shift from a largely agricultural workforce to industrialised employment, is going to be repeated this century as information becomes abundant.

Harnessing the Internet of bees

Cheap and small sensors mean it’s easier to put a chip on something. In this case we have a CSIRO project tracking bee activity where Tasmanian scientists have put tracking devices on bees.

Those tracking devices would have weighed several hundred grams and cost hundreds of dollars ten years ago but today they are small and cheap enough to fit onto the backs of bees.

Being able to deploy these sensors means we can fit them to things we couldn’t have imagined a few years ago and the data they generate is going to give us insights into patterns and behaviours we couldn’t have contemplated.

However not all of this data is useful or necessary and some may even be damaging to individuals and groups. One ethical question we have to ask ourselves is whether it is in the community’s interests to collect this information.

Another aspect of connecting devices, or even animals and people, to the Internet or a network is it opens the possibility of hacking, as we’ve seen in the recent Jeep case where engineers showed they could control a vehicle remotely. The security and privacy aspects of the IoT are critical and something designers and product engineers can’t overlook.

Decoding the data

It’s often said that Data is the New Oil. In truth it isn’t, data is increasingly cheap and easy to access. Being able to analyse that information is where the power lies.

Data analytics is probably going to be one of the most important fields in an information rich economy and already we’re seeing companies springing up to help farmers estimate crop yields, truck drivers plan their routes and even organisations like the Royal Flying Doctor Service using cloud services to better plan their operations.

Again these services plan a lot but there’s also downsides as inappropriate data matching risks breaching consumers’ privacy and even drawing false conclusions from confusing correlation with causation. A good example of this is Facebook being used to judge credit worthiness.

Removing the human element

Automation – whether it’s through robotics, machine learning or algorithms – will change many industries and the workforces employed by them.

One understated field is management where many white collar supervisor jobs are at risk from business automation. It may be that the executive suites are the next sector to be decimated by computers and robots.

Similarly, many services industry jobs such as taxi drivers and baristas are at risk from robotics while large scale 3D printing of buildings threatens to put many building trades under pressure.

No more truck drivers

Driverless vehicles have a whole range of applications, in logistics were seeing them put forklift drivers out of work while mining companies are rolling out massive dump trucks in their new mines that don’t require $200,000 a year drivers.

One study estimates that half the police workforce in the United States would become redundant as law abiding driverless cars become common.

Similarly electric cars will have a massive impact on government revenues. Currently Australian governments raise $17bn a year from fuel excise and has ramifications for businesses involved in the supply chain for service stations.

Once driverless vehicles become commonplace we may well see them changing industries like daycare, public transport and couriers as it becomes possible to summon an autonomous vehicle, put the kids or the luggage into it and then send it off to its destination. If you’re worried, you can track the progress on an app.

The effects of the driverless car show how we have to think laterally about the effects of new technologies on our businesses, sometimes the effects of a new way of doing things could indirectly hurt our business or create new opportunities.

Squeezing out inefficiencies

One of the great promises for the IoT, Big Data and business automation is to remove inefficiencies from industry. Cisco believe that up to 14% of the Oil and Gas industry’s costs could be stripped away with today’s technologies. That in itself is worth over a 100 billion dollars a year in cost savings.

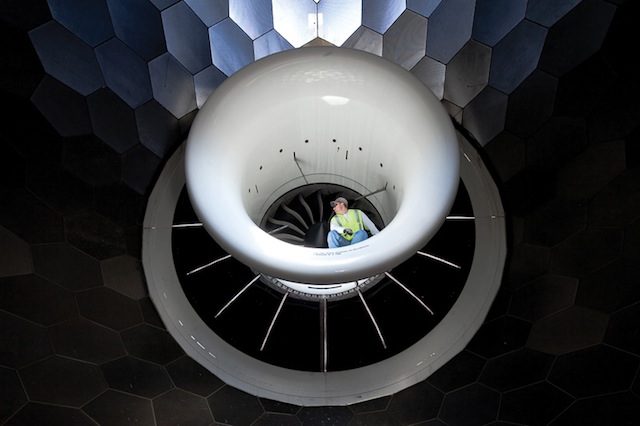

GE are deploying their technologies into a diverse range of industrial equipment ranging from jet engines to railway locomotives and wind turbines with spectacular results in reducing costs and improving productivity.

The effect of these improvements means less downtime and maintenance costs which are good news for customers and shareholder of these companies, but bad news if you’re a maintenance business. It also means the speed of change in business is accelerating.

Skilling the future workforce

In summary the skills needed today are very different to those of 1915 and 1965 and those of the next fifty years will be even different.

As a society we have to decide what skills we are going to give not our children but those currently still in the workforce who are going to be working longer and later into their lives as the workforce ages.

We also have to consider what sort of ethical compass we have. While the technology we have today is powerful and capable of great things, it’s also capable of great harm. We need to have an understanding of what the effects and limits are of our actions with the Internet of Things, Big Data and analytics.

Ultimately we need to ask what value we as individuals can add to our communities and society.

Similar posts: