Such are the vagaries of radio that I’ve been asked to comment on ABC Radio South Australia about foreign ownership based on an article that was picked up by The Drum 14 months ago.

That article was written shortly after Dick Smith came out grumbling about the prospect of Woolworths selling the electronics store chain named after him to foreign interests.

My point at the time was that foreign owners would be preferable to some poorly managed, undercapitalised local buyer as the Australian retail industry – even in a declining market like consumer electronics – needs more innovation and original thinking.

As it turned out, Dick Smith Electronics was sold to Anchorage Capital, a private equity turn around fund with an interesting portfolio of businesses.

In the meantime, the argument about foreign ownership of property and businesses, particularly farms, has ratcheted up as opportunistic politicians and the shock jock peanut gallery that sets much of Australia’s media agenda have found a cheap, jingoistic issue to score points from.

So why is foreign ownership of businesses like farms, mines and factories important for Australia?

A fair price for hard work

The main reason for supporting foreign buyers for Aussie businesses is it gives entrepreneurs a chance to get a fair price for their hard work.

A farmer or factory owner who builds their business shouldn’t have to accept a lower price because Australians don’t want to pay for the asset.

It’s not a matter of being able to pay Australians as have plenty of money to invest – a trillion dollars in superannuation funds and three billion dollars claimed for negative losses in 2009-10 show there’s plenty of money around – it’s just that Aussies don’t want to invest in farming, mining or other productive sectors.

We’re already seeing this play out in the small business sector as baby boomer proprietors find they aren’t going to sell their ventures for what they need to fund their retirement.

Access to capital

Should the protectionists get their way then the businesses and farms will eventually be sold to undercapitalised Australian investors at knock down prices.

This is the worse possible thing that could happen as not only do the entrepreneurs miss out, but also the factories and farms decline as they are starved of capital investment.

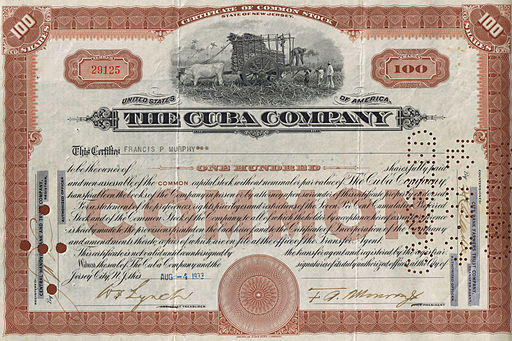

Cubby Station

A good example of both the lack of capital affecting investment and finding a fair price for ventures is Queensland’s Cubby Station.

While I personally think Cubby Station is an example of the economic bastardry and environmental vandalism that are the hallmarks of the droolingly incompetent National Party and its corrupt cronies, the venture itself is a good example of why the agriculture sector needs foreign investment.

Having been converted from cattle to cotton in the 1970s, Cubbie grew as successive owners acquired water licenses from surrounding properties.

Eventually the company collapsed under the weight of its debts in 2009 and the property was allowed to run down by the administrators until it was bought by Chinese backed interests at the beginning of 2013.

At the time of the acquisition, the company’s former chairman told The Australian, “on reflection, I would go into those things with an even stronger balance sheet — in other words, with less gearing.”

In other words, the company was under-capitalised.

Competition concerns

Another reason for encouraging foreign ownership is that Australia has become the Noah’s Ark of business with duopolies dominating most key sectors.

Bringing in foreign owners at least offers the prospect of having alternatives to the comfortable two horse races that dominate most industries.

The property market

An aspect that has excited the peanut shock jocks has been the prospect of Chinese buyers purchasing all the country’s property.

For those of us with memories longer than goldfish, today’s Chinese mania is almost identical to the Japanese buying frenzy of the late 1980s.

Much of what we read about the Chinese buying homes is self serving tosh from property developers and real estate agents and what mania there is will peter out in a similar way to how the Japanese slowly withdrew.

This isn’t to say there shouldn’t be concerns about foreign ownership – tax avoidance, loss of sovereignty and Australia’s small domestic market are all valid questions that should be raised about overseas buyers, but overall much of the hysteria about foreign ownership is misplaced.

What Australians should be asking is why the locals aren’t investing in productive industries or buying mining and farming assets.

The answer almost certainly is that we’d rather stick with the ‘safety’ of the ASX 200 or the residential property market.

We’ve made our choices and we shouldn’t complain when Johnny Foreigner sees opportunities that beyond negative geared investment units or an tax advantaged superannuation fund.