This is the prepared version of my speech at the Cloud Crowd “Can Innovation Save Australia” debate. I was on the affirmative team, even though in truth I’m probably close to the negative side.

Australia truly is the lucky country. We entered the Twentieth Century as one of the richest countries on earth and at the turn of millennium we remained so.

The first fifteen years of this century have been equally kind, however that prosperity has been built on a mining boom and an ever growing property bubble.

Now those foundations are slipping – the mining boom is over and Australians have became the most indebted people on the planet as housing loans put an increasing burden on Australian families, a situation that is not sustainable.

The three Bs of Australian Business

Making matters worse, the good years of the last three decades have seen Australia’s business community become inward looking and complacent, as one of my colleagues recently wrote Australian managers are obsessed with their “Three Bs” – Bonuses, BMWs and their Balmoral Beach Club memberships.

Australia though has a fine history of invention and innovation, we’ve seen ideas ranging from the stump jump plough and Hills hoist through to the flight data recorder and Cochlear ear implants change the world.

Cochlear itself forms the centre of an Australian hearing technology hub at Macquarie University which brings together university researchers, private sector R&D and some of the world’s best medical specialists to form a globally competitive centre of excellence. We can do great things.

Starting from behind

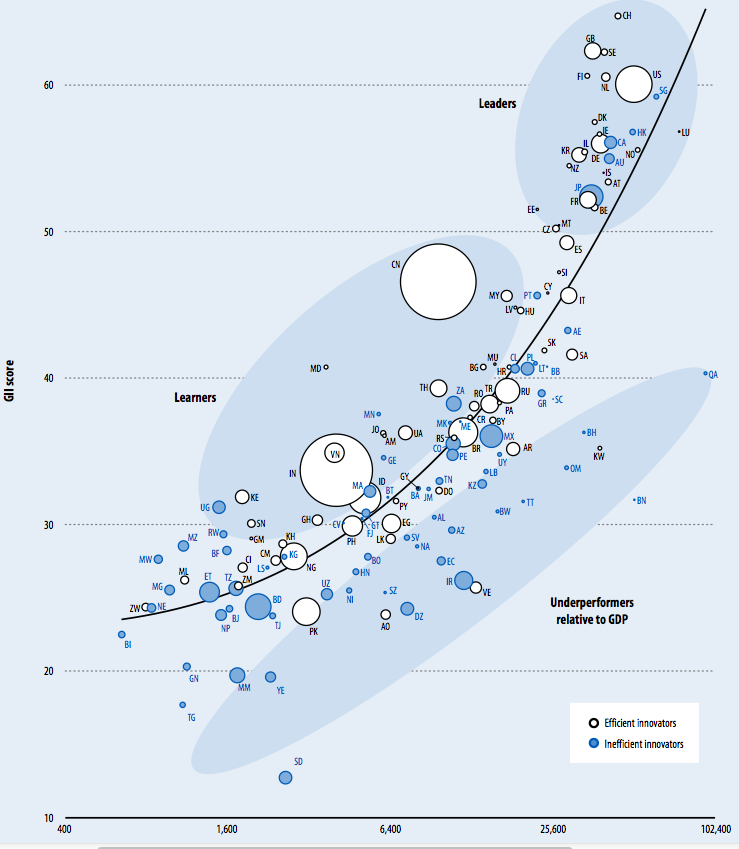

However we are starting a long way behind the rest of the world. Not only is Silicon Valley speeding ahead but so too are countries as diverse as the UK, Israel and Singapore. One of the understated stories in Australian media is just how heavily China is investing in its pivot into a knowledge and innovation based economy. Others in our region like Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Malaysia are already well down the path of moving to economies based on 21st Century technologies.

All of these countries – their governments, their business leaders and the communities – have recognised success in the Twenty-First Century will depend upon investment in education, research, development and businesses that harness the great powers being unleashed by today’s technologies.

This is where Australia’s opportunity also lies. In the 19th and 20th Centuries the country was the beneficiary of technologies like the steam ship, the telegraph, refrigeration, electrification and, at the end of the Twentieth century, the great global financial deregulations. We truly were the lucky country.

Staying lucky

Remaining lucky in the 21st Century is going to take more than riding on the back of sheep, the end of coal train or surfing the wave of easy credit that crashed over our economy in the 25 years after 1990. We are going to have to be smart, canny and adventurous.

Australians though have shown they can grasp opportunities and with government policies that favour innovation over speculation, investment over ticket clipping, a business community that pulls its weight in research and a community that values education at all levels we can do it.

So yes, Innovation can save Australia but we as a nation have to be prepared to work at it and change many of our current ways of thinking.