The Turnbull government and its ministers face a big test in the upcoming innovation statement this week and will need to follow through with tangible results.

In 1976 Clive James visited Sydney fifteen years absence from his hometown. In his book Flying Visits he described the changes that had happened during his time away including some observations on the nation’s thriving movie industry with the comment “premature canonization is the biggest threat facing the young Australian film director today.

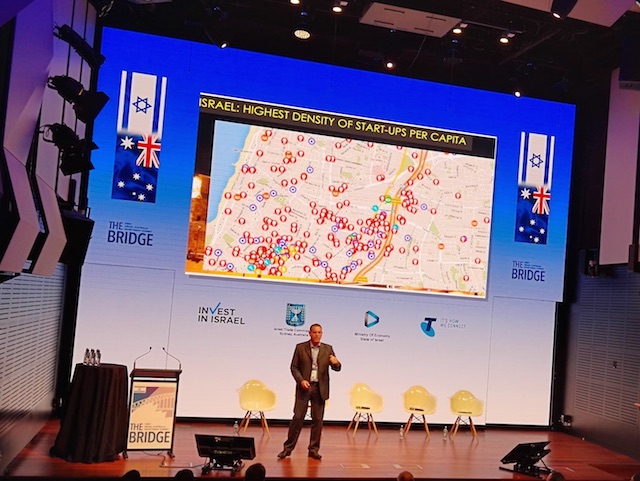

James’ words came back to me at an Australian Israel Chamber of Commerce in Sydney last week where the hosts were gushing over 25 year old Wyatt Roy, the Federal Assistant Minister for Innovation, last week.

There’s a lot to like about Wyatt Roy, he’s an intelligent and articulate minister with a self depreciating sense of humour and a touch of humility – qualities generally not associated with Australian politicians – though the old guard gushing over his youth and the achievements of his two months in office can be embarrassing.

In many ways the fawning over Wyatt Roy is emblematic of the general sense of relief in Australian business now the Turnbull government has left behind the nightmare of the vindictive and petty middle aged adolescents who made up the Abbot administration while also being a world away from the backward looking grey Liberal Party stalwarts of the Howard era and the self interested suburban Labor apparatchiks of the Rudd and Gillard years.

The question though is whether the hopes pinned on Turnbull and Roy can be realised which is why there are so many hopes being pinned on this week’s expected release of the government’s Innovation Statement laying out a policy framework for the nation’s economic pivot.

For Australia the stakes are high, the resource sector is collapsing and the property market – the real key to the nation’s suburban prosperity – is looking brittle. Policies that encourage new businesses and industries are now essential to maintain the country’s living standards.

To date Canberra’s policy makers have not managed the economic changes well; the Intergenerational Report earlier this year blithely ignored the effects of technology on the future workforce and its implications to incomes, jobs and government budgets, while three years after the Gillard government’s Australia in the Asian Century report it’s remarkable how dated the document with its underlying assumption of never ending resources demand now looks.

So the Innovation Statement matters in laying out a strong view for the future of Australia however even if it does prove to be a strong, forward looking document, the Turnbull government will need to follow up with substantial actions.

The real risk with all the talk of innovation is that it will be siloed, along with IT, as “something the geeks and young kids” do. For the this week’s announcement to be anything more than more fine words from the Innovation Bureaucracy then it has to be backed by strong reform to taxation, social security, immigration and corporate governance regulations.

While the canonisation of Wyatt Roy and Malcolm Turnbull may well be premature many Australians, including this one, are hoping those hopes are well founded. This week’s Innovation Statement will be the first test.