In the early 1990s I was working for a British company in Hong Kong and regularly commuting to Taipei. On a Cathay Pacific flight back from Taiwan one Friday afternoon, I found myself on the same flight as the organisation’s Asia-Pacific director who graciously got me into the lounge for a beer.

Over that beer he told me how earlier in the year he’d been asked by one of the pukka English directors why he was bothering spending so much money in business development for ‘third world countries’ like Taiwan and South Korea.

Jeff, as we’ll call the director, laid down a challenge to his board. “Come out and have a look for yourself,” he told them.

Some of the UK based directors took Jeff up and flew out to Hong Kong, first class on BA of course, and then continued on to Taipei where they suitably amazed to be greeted by a first world city.

“They genuinely believed they were going to fly in a DC-3 and be met by a bunch of rickshaw wallas,” laughed Jeff, a long standing English expat. “The Brits don’t get East Asia.”

It seems things haven’t changed much as veteran venture capital investor Mike Moritz made a similar point at a speech in London yesterday that the West doesn’t understand China, particularly Europe.

“People underestimate China, especially in Europe,” Business Insider quotes Moritz as saying. “They have very little sense of the size, strength, and scale of ambition of the leading Chinese technology companies.

Moritz pointed out the fund he leads, Sequoia Ventures, is now placing over half its money in non-US companies with Chinese businesses being high on the list.

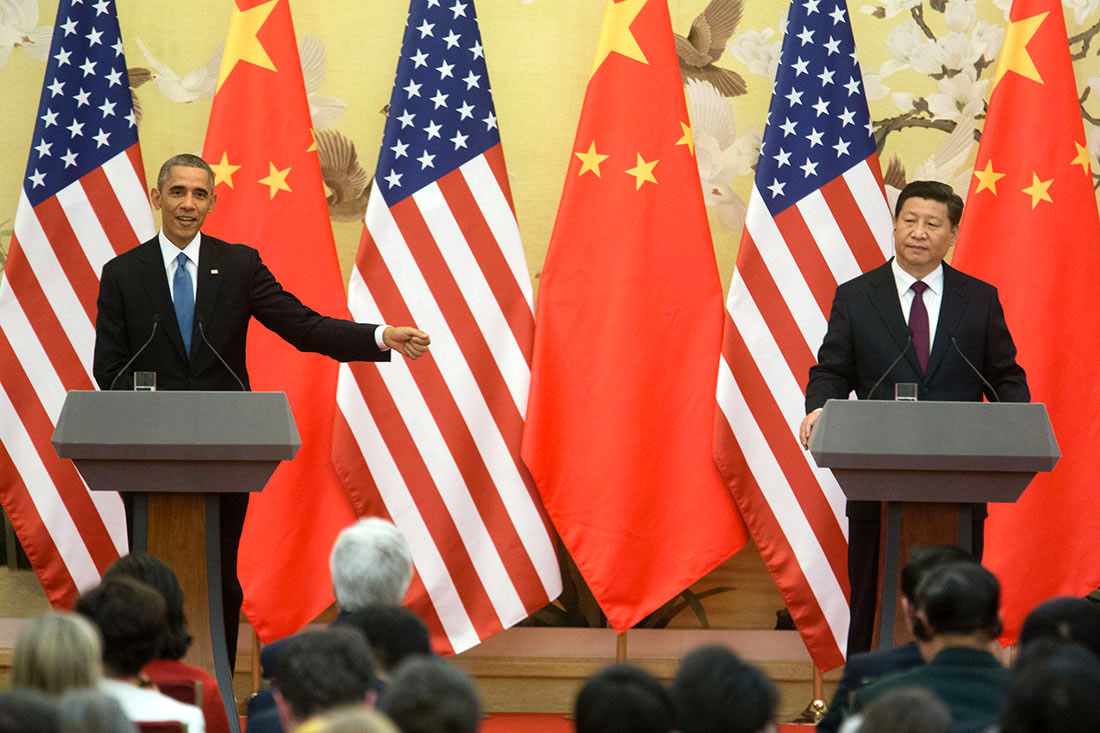

The West’s misunderstanding of China goes beyond business, with The Economist warning that many nations are soon going to have to choose between the PRC and the United States as Beijing sets up its own network of global alliances and trade accords.

So far the United States has responded to this with clumsy efforts like the Trans Pacific Partnership, an attempt to quarantine China’s influence in the Western Pacific that actually gives PRC based businesses a competitive advantage over nations that enter the deal which does little more than strengthen US corporate interests.

Already in Africa, the results of China’s economic efforts are being seen. A good example is the new Ethopian Railway where the Chinese were quick to fund a project that EU and World Bank lenders had dragged their feet on.

Just as English businessmen in the 1990s misunderstood what was going on in East Asia, it seems ignorance of Chinese growth and intentions are even more widespread today. There may be some shocks coming for countries like Australia who assume today’s realities are tomorrow’s.