It bills itself as ‘the coolest little capital in the world’ however something is going on in Wellington, New Zealand’s capital city, as its technology sector takes off.

Last week I was in Wellington, partly to attend the Open Source, Open Society conference and also to have a look at how the city is doing so well as one of the leading startup cities.

While I’ll have a number of posts about the city, startup scene and conference over the next couple of weeks, it’s worthwhile noting some basic impressions that came from the visit.

The size of the city, Wellington is a small town with a population of 200,000, brings both advantages and negatives for the business and startup communities.

Small is sweet

One of the advantages of being so small is the business community is relatively accessible, a number of entrepreneurs told me how easy it is for them to find the specialists they need given there’s usually two degrees or less separation between everyone.

Normally having a small business community means it gets insular, particularly in a capital city where the business of government can create a bubble effect. What’s notable about Wellington is most of the businesses are looking outward towards the US, Australia and East Asia.

The city’s intimate business environment also improves trust within the community as one Aussie expat told me, “if you rip off anyone in this town pretty well everyone knows about it by the end of the weekend. It keeps everyone honest.”

Being small, the city makes it easy to walk around which compounds the business networking opportunities. A businesswoman, who is also a lifelong Wellingtonian, observed how she allows an extra 15 minutes to walk anywhere as she finds herself stopping for conversations.

Three dominant businesses

Having three successful businesses in the city – TradeMe, Xero and Weta – has both its upsides and disadvantages with the bigger players tending to dominate the employment market and funding opportunities.

Of the three businesses, TradeMe is the most domestically focused while Xero is growing in the tech sector and Weta is the most diverse with its range of special effects and movie production services.

With Weta, the business is exposed to the vagaries of the global film industry as Statistic New Zealand survey of movie production shows.

The film industry is one of Wellington’s important employers with the sector supporting around two thousand businesses in the city, although I didn’t get time to explore how much of an overlap there is between the tech and film industries.

TradeMe is largely a domestic focused business that provides a steady work and skills base for the local workforce. While it’s the least internationally exposed business of the three, it’s probably also the most consistent.

Xero, like Weta, is a globally expanding business and its success is attracting investors and expats from North America and Australia. While its the smallest of the three it’s probably the business that has done the most raise Wellington’s profile in the tech industry.

Community spaces

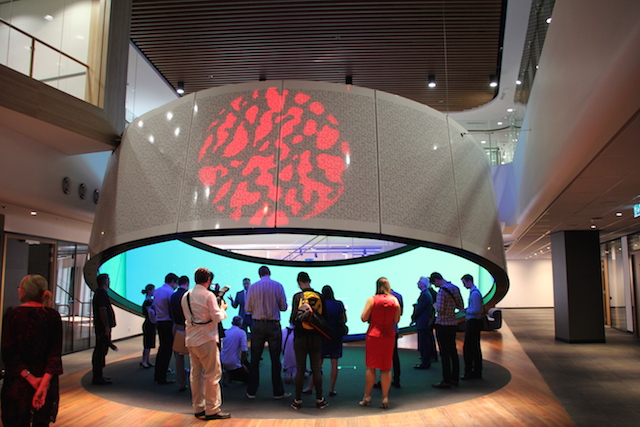

What’s particularly notable are the number of coworking spaces in Wellington ranging from the straightforward Bizdojo startup space and Creative HQ through to the quirky Enspiral coworking space.

The availability of shared spaces makes the city attractive to startups and adds to the vibrancy of the local tech community which links into hipster pursuits such as craft beer.

Communities like Enspiral also add another dimension to the local startup and creative industries environment by connecting entrepreneurs with their peers and service providers.

Partnerships with government

One aspect I didn’t get to explore while in Wellington was the relationship between the city’s business community and educational institutions, particularly Victoria University.

Similarly I didn’t get the opportunity to discover how much of a role local and national governments have had in the development of Wellington’s tech scene. It seems to be relatively hands off although some government agencies have supported Weta with co-investment funds.

What I did meet though were plenty of immigrants; from Croatia, Denmark, Holland, the US and, most of all, Australia.

Talking to some of the US and Australian expats it was clear that lifestyle combined with opportunity with lifestyle, as one Aussie emigre told me “I couldn’t get the water views, access to the city and be able to walk to work back home like I can here.”

While these are superficial thoughts that I’ll expand on over the next week as I decipher notes and listen to interviews, there’s no doubt that Wellington is carving a position as one of the global centres of the new economy. How big it becomes will depend on how many other businesses grow to the size of Xero or Weta.

Similar posts: