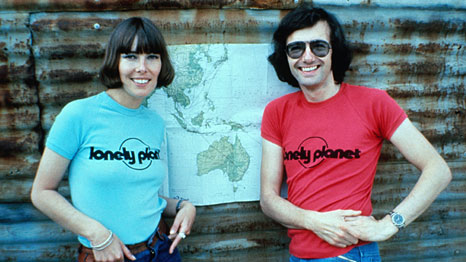

When the BBC bought a 75% of travel guide publisher Lonely Planet in 2007, many people were puzzled at what the travel guide added to the publicly owned broadcaster’s mandate.

In 2011 the BBC bought out the rest of the founders’ stakes and just over a year later management mistakes threaten to destroy the brand.

Lonely Planet is one of the most powerful internet media properties in the English speaking world having become the dominant travel guide in the 1980s and then successfully making the jump into the online world with its website and mobile apps.

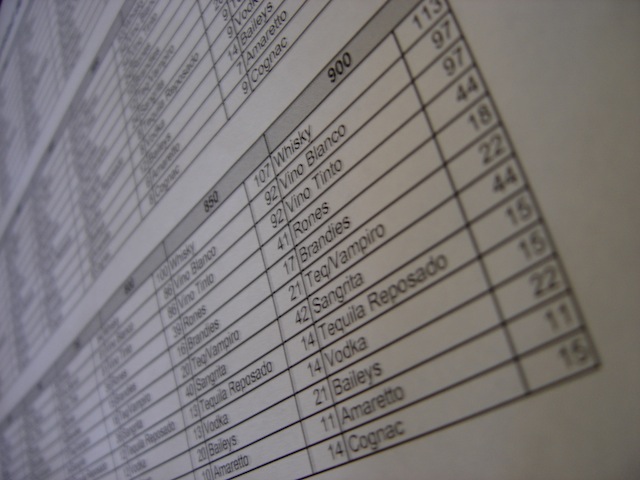

In 2012, the site boasted of four million visitors a month with most under 35 years old.

Key to Lonely Planet’s online success has been its community. The Thorn Tree forum provided the bulk of the site’s traffic as thousands of members discussed exotic destinations and asked or answered travel questions.

The Thorn Tree also turns out to be the BBC’s undoing as management struggled to control members’ comments.

At the end of 2012, inappropriate content was bought to management’s attention, with the Jimmy Savile scandal still reverberating around the corridors of the BBC, the organisation’s management panicked and announced a temporary closure of the Thorn Tree.

Two months later, the site is back up again with strict pre-moderation of posts which has left many long time users upset and going elsewhere, if they didn’t already do so during the closure.

Online communities are a strong assets but they are surprisingly fragile, as many popular sites have found in the past.

For Lonely Planet users, there’s no shortage of other travel sites online and it’s going to be challenging for the site to recover.

The Thorn Tree saga raises the question of whether risk adverse, public sector organisations like the BBC have the risk appetite to run online forums and build communities.

By definition successful online communities are diverse and sometimes skate close to the boundaries of good taste for a careerist executive in a managerial organisation like the BBC, such risks are intolerable and have to be eliminated.

If this means shutting down the Thorn Tree forums or neutering them, then that will be done. Management careers come before the good of the organisation.

Time will tell whether Lonely Planet will continue to thrive under the BBC and its management, but the portents aren’t good.