“Johnny down the street hacked my Minecraft account!” is something almost every parent today has heard in one way or another.

If you believed the kids, the schools are full of 12 year old hacking geniuses that can unravel passwords faster than a CIA super computer.

Usually it turns out the “evil hacker” in Grade 5 had the password all along as the kids share their login details with all their friends.

The New York Times recently pulled together story showing how teenagers are sharing passwords to show their affection. One wonders how many abusive relationships see the dominant partner control the other’s social media and online accounts.

It isn’t just kids and teenagers who find themselves in trouble though, businesses make the same mistakes. Commonly sharing a password to important files and tech functions across the organisation.

Thinking this is just a small business problem would be a mistake; Australia’s Vodafone made all their entire customer base available on the Internet thanks to single logins and shared passwords for each of their dealers.

Over the years this caused major problems for customers and the honest Vodafone dealers as their unscrupulous competitors hijacked accounts and churned clients to new plans. The cost to Vodafone Australia must have been huge but impossible to quantify given they apparently had no tracking mechanism to figure out who had accessed accounts.

In households and business, the main reason we share passwords is convenience – security by nature is always inconvenient. It’s convenient not to bother locking your front door or leaving your keys in the car.

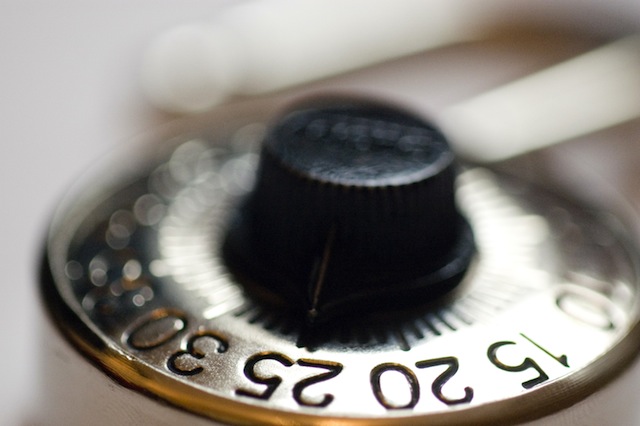

When you really value something, you lock it up and you don’t give a key to everyone in your neighbourhood. It should be the same with passwords, keep them strong and keep them secret.

Our kids learn this the hard way, we shouldn’t have to.