Many of us are still getting comfortable with the idea of 3D printing, but MIT’s Skylar Tibbits is working on a fourth dimension that he hopes will move us into a more elegant era of design.

Ahead of Skylar’s visit to Sydney for the Vivid Festival in June, Decoding the New Economy had the opportunity to interview him about what 4D printing is and his quest to create materials that can build themselves.

What is 4D printing

“We called it 4D printing because we wanted to add the ability for things to change and transform over time,” explains Skylar. “Time is the fourth dimension.”

Skylar’s mission at MIT’s Self Assembly Lab is to create materials that assemble themselves. In a TED presentation he demonstrates how these materials may work and the philosophy behind them.

Part of that search involves developing techniques for building large and complex structures from small components. “People know and utilise this in biology, chemistry and material science domains and we’re trying to translate that into larger scale applications.”

Avoiding big machines

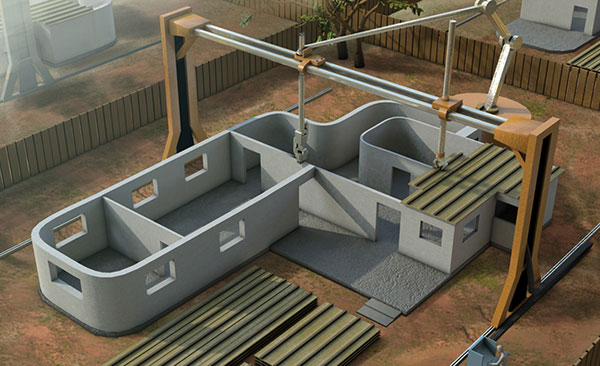

“We don’t want to build bigger machines than the things we want to build, we want to build distributed systems,” Skylar continues. “If you want to build a skyscraper, you don’t want to build a skyscraper sized machine.”

Not only does this philosphy offer benefits for manufacturing and building but it may also save energy, transport and labour costs as things can automatically build themselves once they’re delivered to a customer.

“Materials should be able to assemble themselves or at least error correct or respond to active energy. There’s a whole application of packaging and minimising volume after manufacturing and transforming on site.”

Over time they could also adapt to changed conditions Skylar believes: “There’s also how products themselves can transform and be smarter adapt to my demands or adapt to the environment as it’s fluctuating around.”

Redefining the makers’ movement

Worldwide we’ve seen the rise of the makers’ movement as affordable 3D printing and cheap electronics has made it possible to build new things; Skylar sees the Self Assembly Lab as being part of, but slightly apart from this group.

“We make machines that make things, we’re integrated into that theme. We’re arguing that people can collaborate with materials and materials can be collaborative. It’s not just us making stuff and forcing materials into place, it’s materials making themselves.

“A lot of methods are top down, big machines force materials into place and we’re trying to argue you can have bottom up applications in manufacturing.”

So more than just simply printing components, Skylar sees the opportunity for embedding the intelligence into components so they can assemble themselves; the real task lies in programming the materials.

The internet of elegant solutions

Similarly, Skylar sees the internet of things as being a far more passive, perhaps even friendlier, field than that dominated by machines and plastics.

“It’s not about the number of sensors and electronics and motor and things so that we can make these smart devices, we’re interested in how materials and fundamentally elegant solutions responding to external energy can have the same capabilities.”

“We certainly believe in a connected internet of things, but it’s more a material based internet of things.”

“I think that any solution in the beginning you throw a lot of money, technology and motors at it but over time you find more elegant solutions where materials can do more for you.”

“The wearable space is a good example where people don’t want to wear electronics all over their bodies, they don’t want bulky things that are expensive and hard to assemble and clunky to wear.”

“You want materials that you want your skin to touch, so we’re trying to find elegance in the solutions with smart devices.”

Seeding the forest

The challenge for Skylar, the Self Assembly Lab and those looking at changing the worlds of design and manufacturing is – like many other fields – funding.

Material sciences, particularly those being explored at the MIT, have long lead times that aren’t suited to the current Silicon Valley led model of innovation and Skylar believes we need a different model.

“We need to invest in super, long term radical innovation, to seed the economy and global technology development. We gained substantially in the Silicon Valley model with short term wins – with apps and simple technologies with incremental progress.”

“It’s sort of like we need to seed the forest, we can’t just keep taking all these things from the top like low hanging fruit we need to create a forest effect so that we create many new technologies.”

What comes out that forest of 4D printing and smart materials is anyone’s guess; but if Skylar Tibbits has his way, it will certainly be elegant.

Similar posts: