Musician’s rights advocate David Lowrie has a takedown on his Trichordist of Pandora’s campaign to change the US music royalty payment system through the Internet Radio Fairness Act.

Pandora and other online streaming services claim the current arrangement is unfair and puts them at a disadvantage to terrestrial AM and FM radio stations. Artists and record labels claim this is just a way to cut rights payments.

David suggests that Pandora’s founders either lied about the sustainability of their business at the time of their IPO last year or are just being plain greedy.

Regardless of what is true, or whether David is overstating the case against the IRFA, a truth remains that many Internet business models are unsustainable and Pandora’s may be one of them.

Most unsustainable of all are those who rely on free content.

Eventually the market works to filter out those who won’t pay for content – the good writers and artists move onto something more profitable, like driving buses or serving hamburgers, or they figure out they may as well control their own works rather than let some Internet company profit from their talents and labor.

The website or service offering nothing in return for the contributor’s hard work eventually ends up distributing garbage – Demand Media or Ask are examples of this.

In a marketplace where crap is everywhere, just pumping out more crap is not a way to make money.

Those looking at investing in businesses which rely on free content need to remember this, if no-one values the product then you have no business.

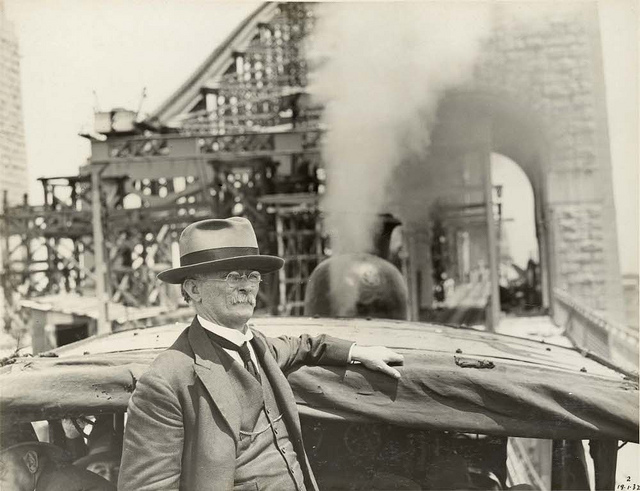

Sadly too many internet entrepreneurs, and corporate managers, believe the road to their wealth is through not paying artists, musicians or writers. They are the modern robber barons.