“Around the world our towncars are usually 30% more expensive than taxis, in Sydney it’s 20% as the cabs are pretty expensive,” said Travis Kalanick on launching the Sydney version of Uber’s hire care booking service.

It’s not just hire cars which are expensive in Sydney – the soaring cost of living in Australia is bourne out by Expatistan, a web site that crowdsources the cost of living in various cities.

Expatisan’s comparisons find Sydney up with Tokyo and London as the most expensive towns on earth.

That conclusion means Australian businesses, governments and policy makers have some important decisions ahead of them.

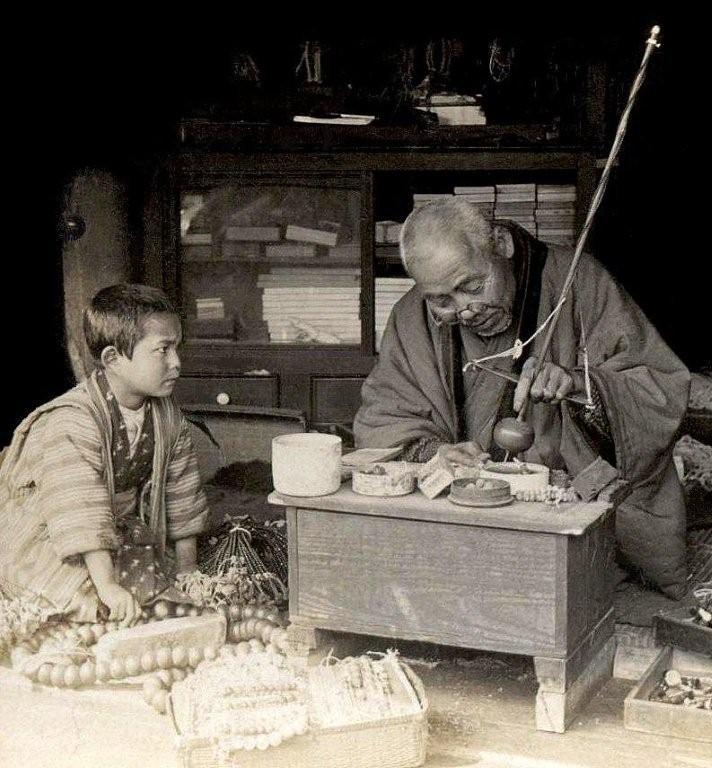

Cholesterol in the veins

High property prices have been the norm for two decades in Australia, the middle class welfare state that both political parties support gives tax and social security concessions to property owners while the banking system requires most business lending to be secured by property.

As a consequence, generations of Australians see property as the only path to financial success. If Bill Gates, or any of today’s entrepreneurial wizz-kids, had been born in Australia, they’d be encouraged to get a safe job and buy property than to take the risk of starting a new business.

The property obsession has another perverse effect in that it creates a short term outlook for Aussie business owners who have to consider getting, and paying off, a mortgage quickly to secure their financial foundations.

A few weeks ago a business owner was profiled in the Sydney Morning Herald, which some call the Sydney Morning Property Spruiker, who paid 1.1 million Aussie dollars (a million US) for a property in Redfern – which is Sydney’s Bronx.

That poor guy not only has a fat mortgage to pay off, but he has to pass those costs onto his customers. Just to pay the bank is a fat chunk out of his business before he pays his staff, landlord and the various other expenses before he can take his profits.

Having to pay the bank for living costs is the main reason why Aussie businesses don’t invest in capital equipment, which in turn makes them less competitive than overseas competitors.

One of the myths in Australian business is that competitiveness is solely due to labor costs, what the ideologues preaching this miss is that even if Aussie workers were paid a bowl of rice a day, Chinese and Mexican factories would still be more productive due to the investment in modern equipment.

For the sake the argument, we won’t even discuss German, Japanese or Swiss manufacturers who are still competitive despite Australian level cost structures.

This last point is what’s missed in much of the discussion about Australia’s economic future – apologists for Reserve Bank governor Glenn Stevens and the self congratulatory Canberra monoculture say that the high Aussie dollar is here to stay and mining will be driving the economy.

Should the mining sector stall, which currently seems to be the case, then housing development will pick up the slack according to the policy-makers’ groupthink.

That housing development is going to come at a high price, with Australian land and homes already among the world’s highest. Given Australia’s private sector debt is among the highest in the world already, it’s hard to see where the money will come from to fuel further property speculation.

Right now Australia has a serious problem in determining what the future will be for the country.

If the future is a high cost economy underpinned by massive property property prices, then the future has to lie in high value added sectors.

The question is ‘what sectors’? Australian business, governments and society in general seem to think that property speculation is the future.

Property speculation turned out not to be the future for Spain and it looks like China’s speculative boom is meeting its obvious end.

Australians are going to have to hope that it really is different down under and that young people and immigrants are prepared to spend huge amounts of money to keep the economy afloat.

If the policy makers are wrong, then the worry is that there is no Plan B.

Similar posts: