This piece originally appeared in The Australian in July 2014. I’m republishing it here given the recent future of work related posts.

For the past four decades it’s been the working class that has suffered the brunt of the effects of globalisation and automation in the workforce. Now machines are taking middle class jobs, with serious implications for societies like Australia that have staked their future on white collar, knowledge-based service industries.

Yesterday, the Associated Press announced it was replacing business journalists with computer programs, following sports reporting where algorithms have delivering match reports for some years.

Some cynical media industry commentators would argue rewriting PR releases or other people’s stories — the model of many new media organisations — is something that should be done by machines. Associated Press’ management has come to the same view with business data feeds.

AP’s managing editor Lou Ferrara explained in a company blog post how the service will pull information out of company announcements and format them into standard news reports.

Ferrara wrote of the efficiencies this brings for AP: “Instead of providing 300 stories manually, we can provide up to 4,400 automatically for companies throughout the United States each quarter.”

The benefit for readers is that AP can cover more companies with fewer journalists, the question is how many people can afford to read financial journals if they no longer have jobs?

Making middle managers redundant

Many of those fields that cheered the loss of manufacturing are themselves affected by the same computer programs taking the jobs of journalists; any job, trade or profession that is based on regurgitating information already stored on a database can be processed the same way.

For lawyers, accountants, and armies of form processing public servants, computers are already threatening jobs — as with journalism, things are about to get much worse in those fields, as mining workers are finding with automated mine trucks taking high-paid jobs.

Most vulnerable of all could well be managers; when computers can automate financial reports, monitor the workplace and make many day-to-day decisions then there’s little reason for many middle management positions.

Removing information gatekeepers

To make matters worse for white collar middle managers, many of their positions are only needed in organisations built around paper based communication flows; in an age of collaborative tools there’s no need to gatekeepers to control the movement of information to the executive suite.

Irish economist David McWilliams — his television series on the rise of the Celtic Tiger, The Pope’s Children, and the causes of the Global Financial Crisis, Follow The Money, are highly recommended viewing – last week suggested that the forces that disrupted the working classes in the 1970s and 80s are now coming for middle classes.

“The industrial class was undermined by both technological change and globalisation, but rather than lament this, many people who were unaffected by this social catastrophe labelled what happened from 1980 to 2010 as the “inevitable consequences” of global competition.” Mc Williams writes.

Those ‘inevitable consequences’ are now coming for the middle classes, asserts McWilliams.

On the right side of progress

While this is sounds frightening it may not be bad for society as whole; the Twentieth Century saw two massive shifts in employment — the shift from manufacturing to services in the later years, and the shift from agriculture to city-based occupations earlier in the century.

A hundred years ago nearly a third of Australians worked in the agriculture sector; today it’s three per cent. Despite the cost to regional communities, the overall economy prospered from this shift.

Answers in the makers movement

The question today though is what jobs are going to replace those white collar jobs that did so well from the 1980s? The Maker Movement may have answers for governments and businesses wondering how to adapt to a new economy.

Two weeks ago President Barack Obama welcomed several dozen leaders of America’s new manufacturing movement to a Maker Faire at the White House, where he proclaimed “Today’s DIY Is Tomorrow’s ‘Made in America’”.

In Singapore, the government is putting its hopes on these new technologies boosting the country’s manufacturing industry in one of the world’s highest-cost centres.

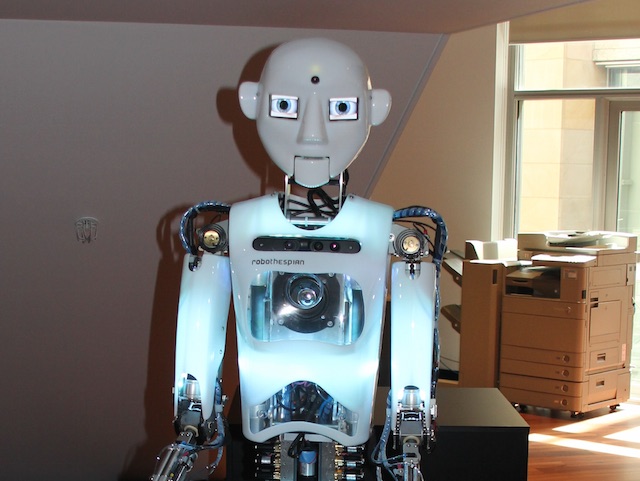

“The future of manufacturing for us is about disruptive technologies, areas like 3D printing, automation and robotics,” Singapore’s Economic Development Board Managing Director Yeoh Keat Chuan told Reuters earlier this year.

Britain too is experimenting with modern technologies, as the BBC’s World of Business reports about how the country is reinventing its manufacturing industry.

Tim Chapman of the University of Sheffield’s Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre describes how the economics of manufacturing changes in a high-cost economy with a simple advance in machining rotor disks for Rolls-Royce Trent jet engines.

“These quite complex shaped grooves were taking 54 minutes of machining to make each of these slots. Rolls-Royce came to us and said can ‘can you improve the efficiency of this? Can you cut these slots faster?’”

“We reduced the cutting time from 54 minutes to 90 seconds.”

“That’s the kind of process improvement that companies need to achieve to manufacture in the UK.”

While leaders in the US, UK and Singapore ponder the future of manufacturing, Australian governments continue to have faith in their 1980s models of white collar employment — little illustrates how far out of touch the nation’s political classes are with reality when they proclaim Sydney’s future as an Asian banking centre or Renminbi trading hub.

Old business ideas

In the apparatchiks’ fevered imaginations this involves rooms full of sweaty white men in red braces yelling ‘buy’ into telephones as shown in 1980s Wall Street movies. In truth, the computers took most of those jobs two decades ago.

As McWilliams points out, the dislocations to the manufacturing industries of the 1970s and 80s were welcomed by those in the professions as the inevitable cost of ‘progress’.

Now progress might be coming for them. Our challenge is to make sure we’re on the right side of that progress.

Similar posts: