Telstra’s Digital Investor report released earlier this week looked at the generational changes for the financial planning industry and the effects of technology on delivering advice and services.

At the core of the report is the projection that by 2030, 70 per cent of Australia’s financial assets will be held by the digitally savvy Generations X and Y and the advice industry is doing little to cater for this group”s media and reading habits.

This is barely surprising, financial planners are one of these fields subject to arcane rules and regulations which make practitioners extremely conservative about innovation or changing work habits, even when the new tools don’t breach any laws.

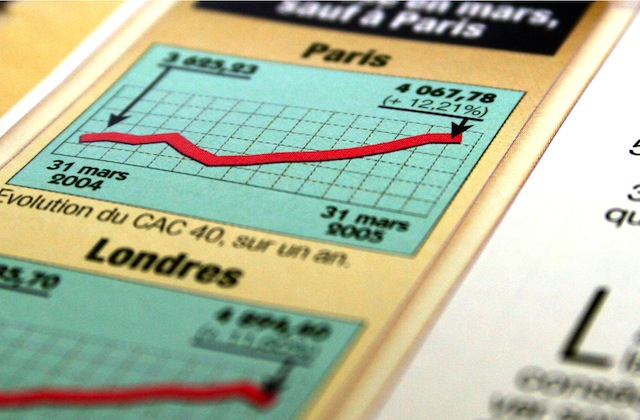

One of the nagging questions though with the report is the underlying assumptions on wealth generation over the next twenty years. Will it really follow the same pattern as we’ve seen for the last few decades?

As the Stanford Graduate School of Management notes in its dissection of the Forbes richest 400 Americans, the path to wealth is changing.

“Three of the 10 wealthiest people in the United States – Bill Gates, Larry Ellison, and Michael Bloomberg – built their fortunes on information technology that barely existed in the 1980s,” says the author Joshua Rauth.

It may well be that the financial planning industry’s core assumptions, of a large, stable middle class workforce steadily squirreling away a nest egg is going to be challenged in an economy undergoing massive change.

Another generational aspect in the Digital Investor report is the handing down of family owned enterprises. The paper quotes social analyst Mark McCrindle saying “Succession planning is already a key issue (for SMEs) – yet by 2020 40% (145, 786) of today’s managers in family and small businesses will have reached retirement age. We are heading towards the biggest leadership succession ever.”

As this blog has described before, many of the current generation of small business owners will never pass their operation on. Their barber shops, car dealerships and factories will retire or die with the proprietor as Gen X and Y entrepreneurs can’t afford to buy the business and the owner can’t afford to retire.

The investment climate of the next quarter century will be very different from the last fifty years as will the business models and the paths to wealth. It’s something that shouldn’t be understated when considering how Generation X and Y will manage their finances.

Despite the weaknesses, the Telstra Digital Investor report is an interesting insight into how one industry is failing to identify and act upon the fundamental changes that are happening in its marketplace.

The financial planning industry isn’t the only sector challenged though and that makes the report good reading for any business trying to understand how marketplaces are changing.