Outliving Our Super is the headline of an Australian Financial Review story on the problems of an aging population.

Jacqui Hayes cites a billboard in San Francisco declaring that life expectancy will soon be 150 and we have to plan for longer retirements.

The flaw in this discussion is the idea of retiring in our 60s. When the age pension was introduced in 1910, a new-born boy could expect to live 55 years and a girl, 59 years. The odds were against the average person every receiving the pension which was an effective, if ruthless, way of ensuring the solvency of social security programs.

A hundred years later, a new born can expect to live well into their eighties. Meaning the average person will spend two decades in retirement.

Making matters worse is the nature of that Millennial’s work pattern – when great, great grandpa entered the workforce in the 1920s, he was almost certainly in his early teens and worked a solid fifty years paying his taxes before prospect of retirement arrived.

Today, that child won’t enter the workforce until at least their late teens and more likely until their early twenties. A modern child is also going to have a much more fragmented work career and will likely have periods of unemployment or low earnings as a casual or contract worker.

For today’s child to retire at 65 it would mean he or she will have had to saved enough over a forty year working life to sustain them for fifteen years of retirement, those numbers are tough and to achieve it most won’t be living the millionaire lifestyle during their golden years.

With a life expectancy of 150, the early twentieth century model of retiring at 60 or 65 means today’s child would spend less than 30% of their lives in the workforce. Put simply, the numbers don’t add up.

The reality is most of us won’t be retiring at 65, the baby boomers reaching retirement age now are learning this and it’s a lesson that’s going to get harder for the Gen X’s and Y’s following them.

As a society, or an electorate, we can pretend there’s no problem and policy makers and politicians will pander to our refusal to face the truth by keeping structures that reflect early Twentieth Century aspirations rather than Twenty-First Century realities.

We have to face the reality that the retiring at 65 is unaffordable dream for most of us. Once we accept this, we can get on with building longer lasting careers.

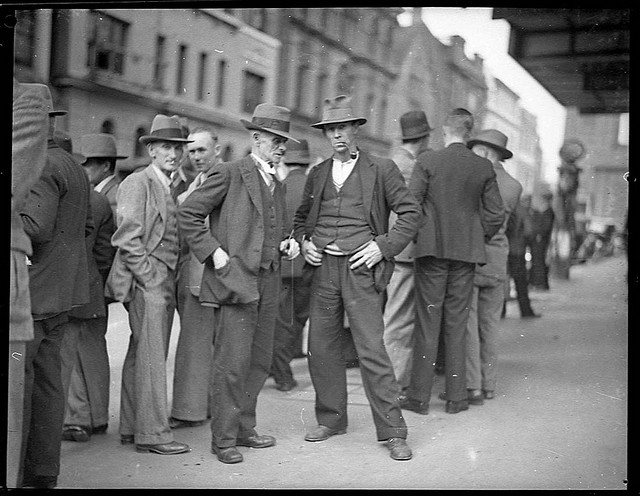

Picture of pensioners courtesy of andreyutzu on SXC.HU

Similar posts: