To say the motor industry is facing disruption on multiple fronts is an understatement.

A global glut of motor vehicles is depressing the world market, a range of emerging manufacturers from China and India are challenging incumbents and a new breed of electric, autonomous vehicles designed by tech companies are arriving on the market.

To cap it all off, today’s young adults in western markets aren’t too interested in buying cars reversing the consumer attitudes which had made the motor industry among the world’s most powerful.

Exacerbating the motor industry’s woes are its antiquated business models, particularly the dealership networks that lock both franchisees and manufacturers into expensive relationships that increase costs, reduce flexibility and do little to add value.

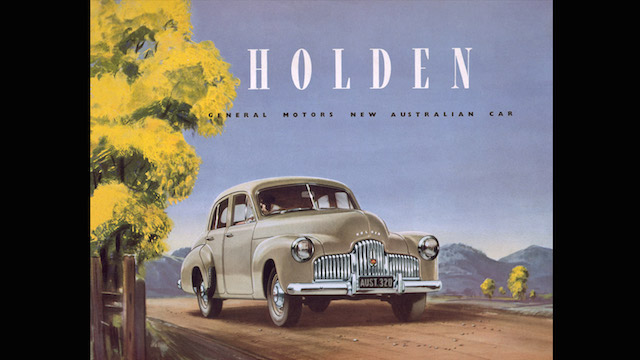

The tale of Australia’s General Motors Holden is a good example, as sales stagnate and the company winds up its Australian manufacturing operations its rationalising its national dealer network.

Unsurprisingly the dealers being axed are less than happy as Wheels Magazine reports.

What’s notable about the story is the level of control the manufacturers have over their franchisees.

Hoffman said Holden had even contacted him to say that once the contract expires, the car maker would send someone to take down $30,000 worth of signage. He will also lose the right to service Holden-badged cars under its capped-price servicing scheme – any cars he sells between now and the day the signs come down, he’s unlikely to see again when service time rolls around. Holden will also buy back any unsold new cars, parts and specialist tools.

That absolute model of franchising had value when the manufacturers’ brands were strong and consumers were born into a ‘Ford’, ‘General Motors’ or ‘Chrysler’ family. Today, the brands are largely interchangeable outside the premium or luxury markets and attempting to lock-in customers is increasingly difficult.

More telling is the inflexibility of pushing stock out to the dealers which may or may not get sold while centralising marketing. The resulting disconnect between consumers and supplier means increased costs and a slow response to changing market conditions.

The motor industry was one of the defining businesses of the Twentieth Century, affordable motor cars changed every society and transformed the cultures of affluent nations.

Now that influence is waning and it remains to be seen how today’s incumbent manufacturers will evolve, if they survive at all, in today’s very different society.

One thing is for sure – the existing dealership structure won’t be around for much longer.