One of Australia’s leading retailers, Solomon Lew, joined the conga line of business whiners this week with complaints that the recently departed Labor government had been bad for his industry.

Yesterday I posted an interview with Susan Olivier of Dassault Systemes about how the retail and fashion industries – Solomon Lew’s businesses – are being radically changed by technology and changing consumer behaviour.

Lew, along with most Australian retailers, has completely missed these changes and instead remained focused on their 1980s model of screwing down suppliers while charging customers high prices for poor goods and substandard service.

Now that 1980s business model has come to an end Lew and his other retailers like David Jones’ Paul Zahra, Myer’s Bernie Brookes and, most vocal of all, Gerry Harvey bleat about government taxes, high labour rates and almost anything else apart from the obvious factors they can fix themselves.

Bigger storms ahead

Along with the two factors Olivier identified, there’s two much bigger factors threatening Australian retail – the tapping out of the credit boom and the aging population.

The aging population is simple, consumer tastes are changing as the population ages and the need for conspicuous consumption and the latest fashions tapers off as one gets older. The demographic boom of the late Twentieth Century is over.

More immediate though is the tapping out of the credit boom, since the Global Financial Crisis Australians have swung around to be net savers which immediately pulls a large chunk out of the discretionary consumer spending pie which had kept the retail industry ticking along through the 1980s and 90s.

Another aspect is the end of the home ATM – while Australian Exceptionalists deny this happened down under, it certainly did as banks sought to ‘liberate’ the equity householder had locked in their properties. This too fuelled the credit boom.

Perversely we may be seeing the home ATM receiving a reprieve as Australian property prices accelerate from their already bubble-like levels, however that short term sugar hit for retailers and the economy is only creating bigger problems for the country’s merchants.

Funding an uncompetitive economy

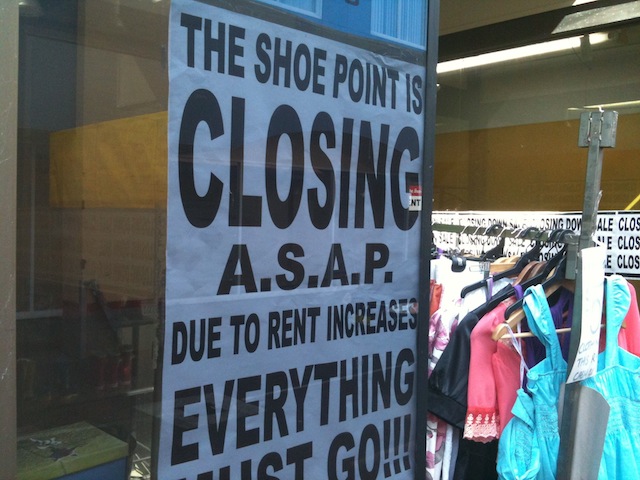

Contrary to the bleating of Australian retailers, the biggest problem facing the sector is the nation’s high rents and property prices.

For consumers, those huge rents and huge mortgages take money that could otherwise be buying more consumer goods, at the same time retailers are being slugged by some of the highest rents in the world, pushing up their costs and reducing competitiveness.

That lack of competitiveness is affecting all parts of the Australian economy, particularly tourism, and the retail industry isn’t immune to those forces.

Anyone who visits an Australian eating establishment will have experienced this, personally I had another experience last night at a pub that charged $4 (3.70 US) for a soda water.

This wasn’t a trendy downtown bar but a pub in a lower middle class suburb with two overworked and under trained young bar staff. During the three hours there, our table of six was cleared once.

Swiss prices coupled with service that would be barely acceptable in a 1970s outback Queensland roadhouse is not the formula for a successful economy.

The business challenge

Which brings us back to Solomon Lew’s whinge about the government, Sol handily overlooks the previous government’s stimulus packages which kept the nation out of recession and put money straight into his and other retailers’ pockets.

There’s a lesson there for the Australian Labor Party that the tweedle-dum, tweedle-dumber strategy of offering near identical corporate and middle class welfare policies to the Liberal Party is not going to win you friends with the nation’s business sector and its entitled leaders.

For the incoming Liberal government, it is faced with the challenge of making Australia a competitive, high-cost economy along the lines of Japan, Switzerland or Germany.

It’s hard to be optimistic about the Abbott government meeting this challenge given the bulk of its ministers are holdovers from the previous Howard Liberal government that was largely responsible for Australia flunking the transition to being a high cost economy along with institutionalising a middle class welfare culture into Australian society.

Even if Abbott does genuinely attempt to address Australia’s lack of competitiveness, he can be sure he will get absolutely no help from the whingeing captains of the nation’s industries, as Solomon Lew has shown.

While Solomon Lew and the Australian managerial class struggle with their perfect storms of economic, demographic and technological change, the nation also faces those headwinds.

Hopefully for Australia there are capable leaders who can navigate those storm waiting to take the helm.

Similar posts: