The catastrophe facing the economy from the necessary closing of industry in the face of the COVID-19 outbreak has dawned on the Australian government. But we have a long way to go.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s belated and inadequate Jobs Keeper package announced today is the first step in addressing the greatest economic crisis facing Australia since Federation and this package will be almost be widened, simplified and bought forward well before payments are scheduled to kick in at the beginning of May.

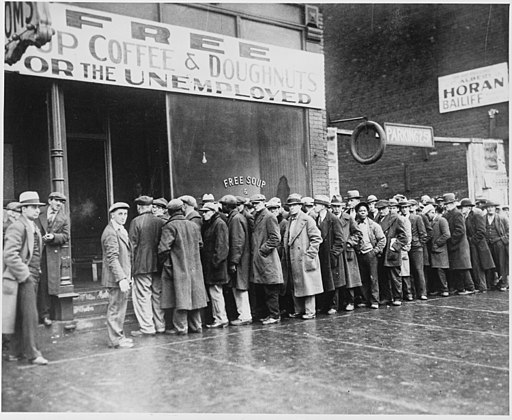

In 2008, the aim of stimulus and support packages was to avoid the very situation we find ourselves in now — widespread business collapses and long unemployment queues. We’re one step beyond where governments were a decade ago.

The size of the collapse should not be understated, looking at the composition of the Australian workforce, we can see exactly how great the damage has been over the past two weeks with two sectors – tourism and hospitality – taking the immediate hit

| Industry of employment (Division) | Feb-19 (‘000) |

| Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing | 332 |

| Mining | 251.7 |

| Manufacturing | 872.5 |

| Electricity, Gas, Water and Waste Services | 147.6 |

| Construction | 1,153.90 |

| Wholesale Trade | 390.9 |

| Retail Trade | 1,284.70 |

| Accommodation and Food Services | 907.1 |

| Transport, Postal and Warehousing | 666.1 |

| Information Media and Telecommunications | 220.4 |

| Financial and Insurance Services | 445.5 |

| Rental, Hiring and Real Estate Services | 216.3 |

| Professional, Scientific and Technical Services | 1,115.30 |

| Administrative and Support Services | 414.1 |

| Public Administration and Safety | 858.5 |

| Education and Training | 1,032.40 |

| Health Care and Social Assistance | 1,702.70 |

| Arts and Recreation Services | 247.4 |

| Other Services | 515.7 |

| Total employed | 12,774.60 |

Source: ABS, Labour force, detailed, quarterly, Feb 2019, cat. no. 6291.0.55.003 (Table 04)

Given the widespread shut downs over the past three weeks, it would be conservative to estimate a million jobs have been lost across the Accommodation and Food Services, Retail Trade, and Arts and Recreation sectors.

With the near shutting down of the Australian aviation industry and the laying off of nearly 30,000 workers by Qantas and Virgin, it would be conservative to say at least 20% of the Transport, Postal and Warehousing sector have lost their jobs as well, despite the demand on logistics chains as shoppers panic buy.

Similar disasters are looming in other sectors including, perversely, Health Care and Social Assistance as areas like day care and private hospitals start to close.

All of which makes the Federal Government’s dithering with support packages for industry, workers and small business more tragic. The delay in bringing in today’s package, at least a week late, has been a disaster for the economy.

The idea payments won’t start until the first week in May is laughable, the drag on the economy, and the human tragedy of thousands of failed businesses in the meantime means it will almost certainly be bought forward with the 30% turnover fall requirement being dropped

If it wasn’t obvious during the slow and muddled response to the bushfire crisis, it’s clear Australia’s leaders struggle with an emergency, and this one has a long way to go.

With the economic crisis threatening to go a lot longer than the pandemic, there will be a lot more money spent and already we’re hearing the cries of ‘who will pay for this?’

One lesson from the 2008 crisis was the cost of austerity to pay for the support and bail outs. Hopefully Australian politicians can learn from Europe’s mistakes and avoid Austerity although that will challenge the Liberal and Labor parties’ modern ideology.

We have a long way to go on this.