One of the hoped for futures of publishing was cheap, hyperlocal websites that report news on individual suburbs or neighbourhoods and get advertising from local businesses.

Last week US TV network NBC abruptly closed down its Everyblock online service, leaving loyal users angry and bemused. Right now it appears though the hyperlocal concept isn’t working.

The failure of Everyblock

Founded five years ago, Everyblock had an interesting model of mashing up local data like Flickr pictures and government information with news so residents and visitors would have an accurate up-to-date picture of what was happening in their neighbourhood.

Everyblock’s failure follows AOL’s struggle to get their hyperlocal play Patch working, although AOL reported in 2012 that Patch’s revenues have doubled.

Whether that doubling is enough to save Patch remains to be seen, it’s quite clear that some question the sustainability of AOL’s growth in revenues and page views.

All of this raises the question of why hyperlocal isn’t working.

A game for amateurs

The main reason is that there’s not enough money it –anybody who is going to run a hyperlocal site is going to be doing it for love or because there’s a dumb corporation burning shareholders’ equity on the venture.

In most communities there simply aren’t enough advertisers interested to pay the bills and you can forget any paywalling.

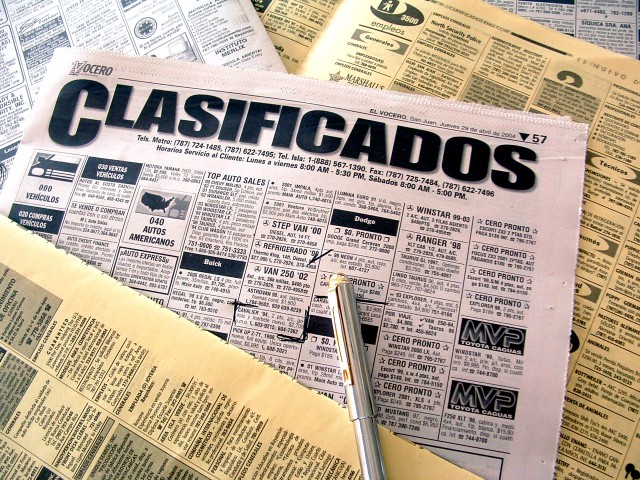

Most critically for local publishing ventures, the local advertising market has been suffocated by the web. Twenty years ago, the local plumber or cafe would hit most of their market by spending $2,000 on their Yellow Pages listing and probably double that with a weekly ad in the classified section of the local newspaper.

Today, a web site with sufficient SEO smarts to come up on their first page of searches for their suburbs is enough, many can get away with a free Facebook or Google Plus for Business page, despite the dangers of using other people’s services to promote your business.

For the telephone directories this change has been catastrophic while local newspapers only survive thanks to their less than healthy relationship with real estate agents.

Local market failure

The interesting thing with the evolving local media market is just how poorly the web giants have performed.

Two years ago, Google appeared to have the sector sown up with the Google Places service but a combination of poor service, restrictive rules and an obsession with Google Plus have seen the company squander their advantage, leaving their local search service underused and irrelevant.

Similarly, Facebook looked like they could take that market off Google but they too haven’t executed well.

Which leaves local businesses reliant on their own websites and a hodge-potch of services like Yelp!, Tripadvisor and Urbanspoon.

This doesn’t serve the business or the customer well.

Where to for local news?

A bigger question though is where do people go to find local news?

Increasingly it looks like social media sites like Facebook and Twitter are the place as people see what their friends and neighbours post. It’s not great, but it’s better than the local newspapers increasingly stuffed with syndicated content with a few local stories from an overworked part-timer.

It’s not clear that hyperlocal news has failed, but right now it’s not looking good. Perhaps it needs somebody with a truly disruptive model to find what works in our communities.

image courtesy of davidlat on sxc.hu

Similar posts: