This story originally appeared in Business Spectator on 17 June 2013

At the beginning of this century, Melbourne hosted a meeting of the World Economic Forum. Among the visiting luminaries was Microsoft founder Bill Gates who laid out his vision for governments in the digital economy.

“The Government itself needs to become a model user of information technology,” Gates said at the time.

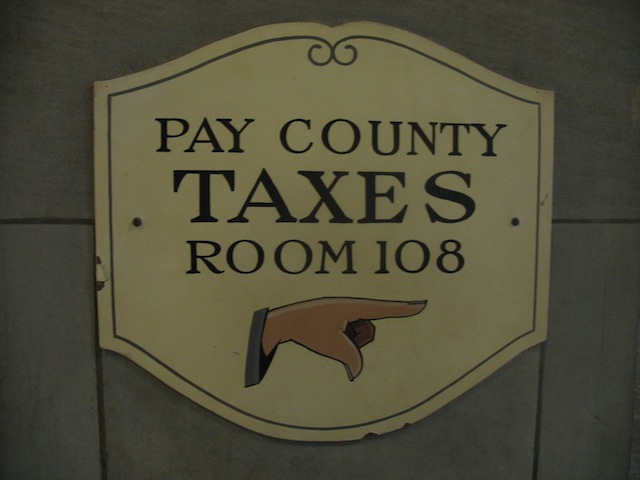

“Literally seeing government work with its citizens, with its businesses will change how we do our taxes, licences, registrations, all these things, on a basis where you don’t have to know the organisation of government and its various departments, you don’t have to stand in line, you don’t have to work with paperwork.”

Last month in Brisbane, the Federal government re-released their Digital Economy Strategy with the ambitious goal to make Australia a “leading digital economy by 2020”. A key part of the strategy is for the government to allow citizens to “fully complete priority services online”.

Thirteen years after Bill Gates articulated the need for governments to move services online – and he was by no means the first person to do so – the Federal government has posted a target to partly achieve this by the end of the decade.

It’s hard to see how achieving such a belated objective will put Australia in a position of leadership in a rapidly changing world, although this is a direct consequence of deliberate decisions made by the nation’s leaders, and society, over the last thirty years.

Thirty years ago the debate on Australia’s position in the global economy resulted in the Hawke government’s Clever Country policies. In many ways, today’s Digital Economy Strategy is an echo of the Labor’s halcyon days under Paul Keating.

Keeping things in perspective

In Sydney on the day before re-releasing the strategy, Minister Conroy channelled Paul Keating in talking about the J-Curve of technology adoption at a lunchtime panel with the Australia Israeli Chamber of Commerce.

Preceding Senator Conroy’s panel was Anna-Maria Arabia, general manager of the Questacon National Science and Technology Centre in Canberra, who described her trip to Israel to look at how the nation that derives 40 per cent of its export incomes from high tech industries is nurturing its technology sector.

Arabia was accompanying Federal minister Bill Shorten and she described a meeting with the chief scientist of the Israeli Ministry of the Economy, Avi Hasson, where Shorten asked him about the success rate of Israeli government research and development projects.

Hasson’s reply was very different to the risk averse response often heard from Australian bureaucrats, ministers and business leaders.

“Had I been told that we enjoyed an 80 per cent success rate I would have concluded the government was investing in the wrong projects,” Hasson is quoted as saying. “Such a success rate would have meant we were investing in low risk projects and, quite frankly, the private sector could have taken care of that.”

The risk-reward equation

In Australia, there is no such vision or appetite for risk. At best the Federal government has announced another review of tax rules and industry support programs while the opposition is vague on its plans to support innovation and R&D should it occupy the Treasury benches later in the year.

While it’s easy – and fair – to criticise both sides of politics, the business sector is equally negligent with its reluctance to invest in research and development while claiming R&D tax credits for projects that are closer to capital improvements rather than real innovation.

Two weeks ago the ABC Business Insiders program had featured an interview between Business Spectator’s Alan Kohler, Dow Chemical CEO Andrew Liveris and Australian Business Council chief Tony Shepherd where they discussed Australia’s role in the modern global economy.

Australian born Liveris, who is also chairman of the US Business Council and sits on the Obama’s board of innovation, said Australia needs a vision building on the country’s strengths.

At present he warns the country is in a state of rigor mortis having “lost the will to innovate.”

Thinking beyond mining

When Gates visited Australia in 2000, he warned that the nation needed to think beyond mining and agriculture and secure a place in the high tech economy.

That warning was disregarded and Australia as a nation made the decision to focus on domestic consumption driven by rising property prices and mining exports.

Reserve Bank of Australia governor Glenn Stevens summed up that national decision in a speech made to the Australian Industry Group in 2010 where he dismissed Bill Gates’ warning about ignoring high tech industries at the beginning at the decade.

“Ten years on, though, it does not seem to have been to Australia’s disadvantage not to have built a massive IT production sector,” Stevens sneered. “On the contrary, the terms of trade are at a 60-year high, the currency just about equals its American counterpart in value and we face an investment build-up in the resources sector that is already larger than that seen in the late 1960s and that will very likely get larger yet.”

Stevens’ speech illustrates the Australia we have today – high-tech industries along with the research, development and innovation are something other countries do.

The vision for Australia being a global leader in the digital economy by 2020 is a laudable and equal to any of the noble objectives proposed in the Gonski education review or the Asian Century report.

Unfortunately to achieve those aims, and to overcome the deliberate national decisions we’ve made over the last thirty years, it’s going to take more than the modest and belated objectives of last week’s re-released Digital Economy Strategy.