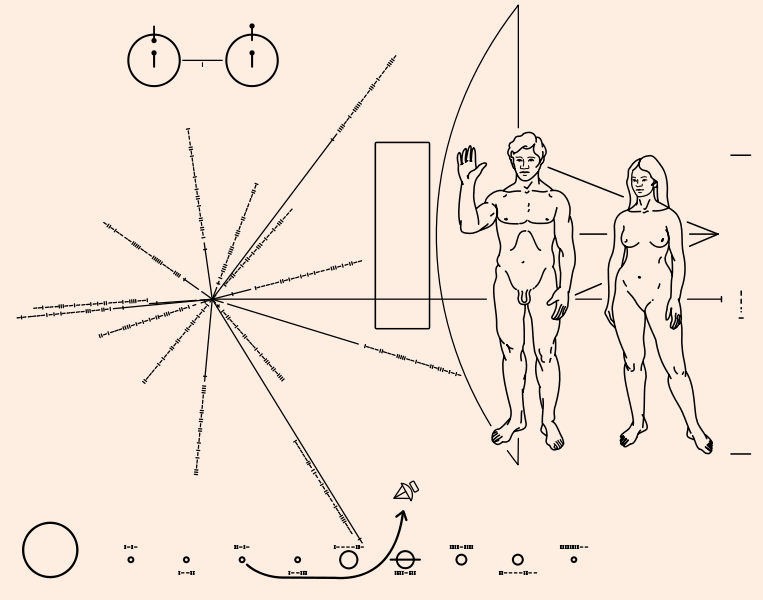

In 1977 NASA’s Voyager mission launched from Cape Canaveral to explore the outer solar system, included on the vessel in case it encountered other civilisations were a plaque and a golden record describing life on Earth.

The record was, is, “a 12-inch gold-plated copper disk containing sounds and images selected to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth.” It containing images, a variety of natural sounds, musical selections from different cultures and spoken greetings in fifty-five languages.

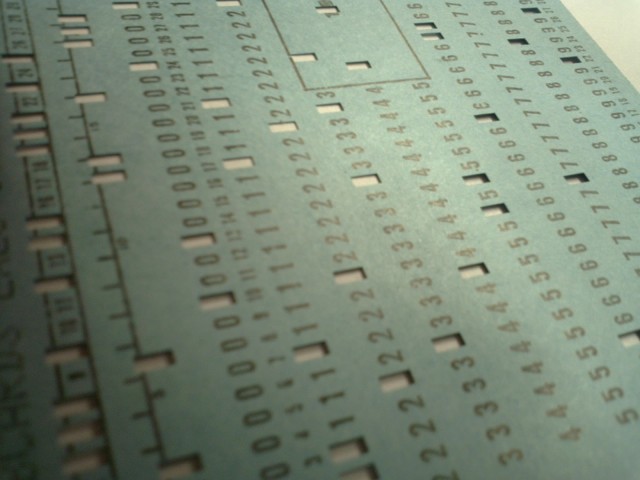

Most American households in 1977 could have listened to the sounds on Voyager’s golden disk but were the spaceship to return today it would be difficult to find the technology to read the record.

This is the concern of Google Fellow and internet pioneer Vint Cerf who told the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s annual meeting in San Jose this week we are “facing a forgotten century” as today’s technologies are superseded rendering documents unreadable.

A good example of ‘bit rot’ is the floppy disk – the icon used by most programs to illustrate saving files is long redundant and few organisations, let alone households, have the ability to read a floppy disk.

For corporations the problem of dealing with data stored on tape is an even greater problem as proprietary hardware and software from long vanished corporations becomes harder to find or engineer.

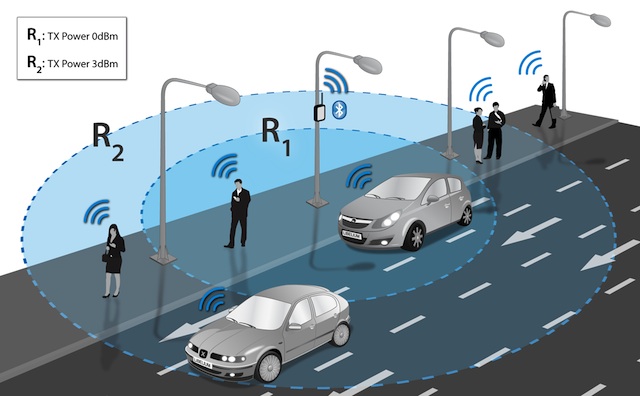

As the Internet of Things rolls out and data becomes more critical to business operations, the need for compatible and readable formats will become even more important for companies and historical information may well become a valuable asset.

With libraries, museums and government archives having digitised historic information, this issue of accessing data in superseded formats becomes even more pressing.

It may be that important documents need to be kept on paper – although there’s still the problem of paper deteriorating – to make sure the 21st Century doesn’t become the digital dark ages and our golden records remain unread.