Last March the Australian internet industry celebrated twenty years of commercial operations with the Rewind/Fast Forward conference that looked at the evolution of the online economy down under and its future.

Naturally the Internet of Things was an important part of the discussion looking at the internet’s future and one of the panels examined the effects of the IoT on industry and society.

During the session chairman of the Communications Alliance industry association, John Stanton, raised an important point about how the IoT creates problems for existing laws and the regulators as a wave of connected devices are released onto the market place.

The risks are varied, and Stanton’s list isn’t exhaustive with a few other aspects such as liability not explored while some of the issues he raises are a problem for other internet based services like cloud computing and social media.

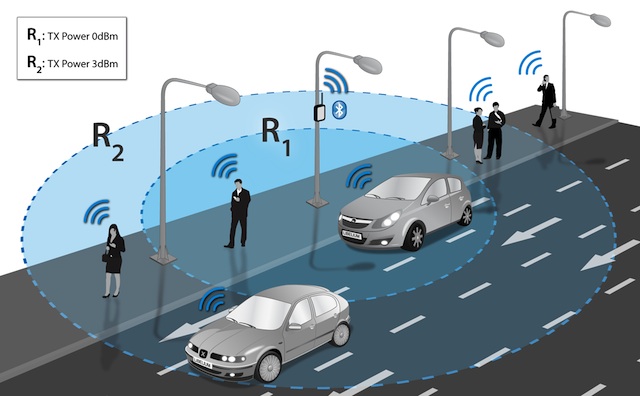

Roaming rules

Having fought many regulatory battles over roaming charges and access between networks, it’s not surprising Stanton and the Communications Alliance would raise this as an issue.

Dealing with roaming devices will probably be a big challenge for mobile Machine to Machine (M2M) technologies, particularly in the logistics, airline and travel industries. We can expect some bitter billing battles between clients and their providers before regulators start to step in.

Number schemes

Again this is more an issue for mobile M2M consumers. Currently every SIM card has its own phone number once the service is activated. It may be that regulators have to revise their numbering schemes or allow providers to use alternative addressing methods to contact devices.

Data sovereignty

Where data lives is going to continue to be a vexed issue for cloud computing consumers, particularly given the varied laws between nations.

Short of an international treaty, it’s difficult to see how this problem is going to be resolved beyond companies learning to manage the risks.

Identity management

Data integrity is essential for the IoT and accurately determining the identity of individuals and devices is going to be a challenge for those designing systems.

Over time we can expect to see some elegant and clever solutions to identity management in the IoT however masquerading as a legitimate device will always be a way malicious actors will try to hack systems.

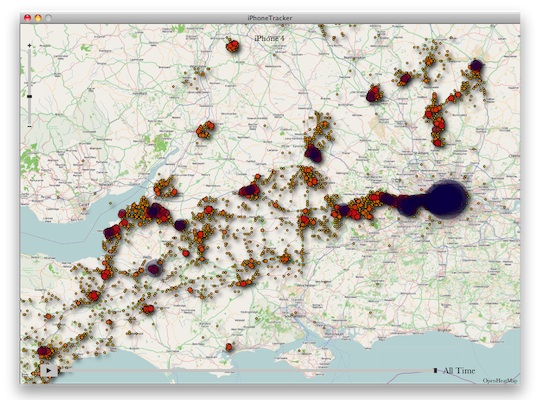

Privacy

For domestic users, the privacy of what remains in data stores is going to be a major concern as domestic devices and wearables gather greater amounts of personal information. We can expect laws to be tightened on the duties and obligations of those collecting the data.

Access Security

Who can do what with a networked device is another problem, should a malicious player or a defective component get onto the system, the damage they can do needs to be minimised. What constitutes unlawful access to a computer network and the penalties needs to be carefully thought out.

Spectrum allocation and cost

Governments around the world have been reaping the rewards of selling licenses to network operators. As the need for reliable but low data usage IoT networks grows, the economics of many of the existing licenses changes which could present challenges for both the operators and governments.

Access to low cost and low data access networks

Following on from the economics of M2M networks, the question of mandating slicing of scarce spectrum for IoT applications or reserving some frequencies becomes a question. How such licenses are granted will cause much friction and many headaches between regulators and operators.

Commercial value of information

How much data is worth will always be a problem in an economy where information is power and money. This though may turn out to be more subtle as information is only valuable in the eyes of the beholder.

Where information becomes particularly valuable is in financial markets and highly competitive sectors so we can see the IoT becoming part of insider trading and unfair competition actions. These will, by definition, be complex.

Like any new set of technologies the internet of things raises a whole new range of legal issues as society adapts to new ways of doing business and communicating. What we’re going to see is a period of experimentation with laws as we try to figure out how the IoT fits into society.

Similar posts: