In last week’s Federal budget the biggest news for business was the expansion of the accelerated depreciation limits where items up to $20,000 can be immediately claimed as a tax deduction.

While this was a reversal of the previous budget that slashed the previous allowance, it was welcome news for businesses looking at replacing older tools and equipment or investing in new technology.

One of the notable things about business technology is companies have a habit of holding onto older equipment long beyond what should have been its use by date.

The consequences of using old technology are real, the older equipment is often not as fast as the newer kit which affects productivity and unpatched software is often the way malware finds its way into a business.

Point of sale risks

Earlier this week computer security vendor Trend Micro held their Cybercrime 2015 breakfast in Sydney where the director of the company’s TrendLabs Research division, Myla Pilao, described some of the threats facing businesses.

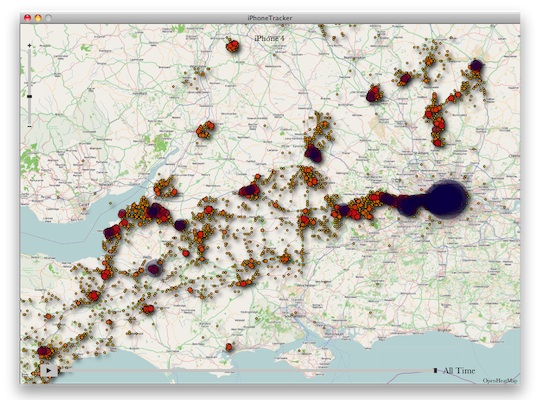

One of the top risks were Point Of Sale systems (POS) where Trend Micro’s research had found over a third of US retailers had malware on their cash registers, in Australia it was six percent.

Most of those infected POS terminals would be older units with many of them being software running on out of date versions of Windows that haven’t been patched or upgraded since they were bought a decade ago.

Similar problems exist with older workstations, internet routers and even photocopiers where the technology has moved on and security holes discovered. Basically old equipment holds businesses back and exposes them to risks.

Now the carrot of an immediate tax deduction gives Australian businesses an opportunity to refresh their technology. So what is the technology, smart company managers and owners should be spending their money on?

Kick out your desktops

“If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” is the mantra for most business IT and desktop computers are the best example of this. In most companies as long as the word processing software or accounting package works the PCs continue to be used.

With the withdrawal of support for the decade old Windows XP operating system last year, many older computers started being a liability in a business so now is the time to replace them.

Consider tablets

It may not be necessary to replace the old desktop computer with new ones, for many job roles a tablet computer is often a better choice. With cloud technologies increasingly being adopted there’s less of a need for a grunty PC sitting on each staff member’s desk.

Upgrade the router

One of the areas where businesses often compromise is with their internet access. Having an old, cheap router designed for home use is just not good enough for companies who rely upon being connected.

A new business grade router will improve office internet access along with resolving most of the security issues older equipment is notorious for.

Going mobile

If you’re struggling on old mobile phones, now might be the time to upgrade to the latest smartphone. Amongst other things this will improve your office productivity, particularly if you combine the investment with some of the cloud services that make working on the road a lot easier.

Cloud services are not part of the depreciation rules as they are usually subscription models and this shows the weakness in the Federal government’s thinking.

Indeed for those vulnerable Point of Sale systems, a cloud based service running on tablet computers is probably a better solution than most server and PC based packages.

A lack of vision

The ‘ladies and tradies’ theme of the budget shows the Federal government is stuck in with the vision that Australian businesses are mainly mom and pop service operations in the traditional trades and professions.

While the depreciation changes are welcome they do little to help startups or companies in emerging industries and for the economy in general will provide not much more than a GDP ‘sugar hit’ for retailers’ cash registers as we buy imported equipment for our businesses.

For the Australian economy in general, the move really only benefits Gerry Harvey who can buy a few more racehorses from his stores’ and his rich mates who can afford some more expensive wine fuelled brawls in Sydney waterside restaurants.

Australian businesses owners need to be demanding better thought out policies from a government that claims to be friendly to industry. The economy is changing and 1970s style tax benefit is not the way to prepare for a changing world.

In the meantime, enjoy your tax write offs.