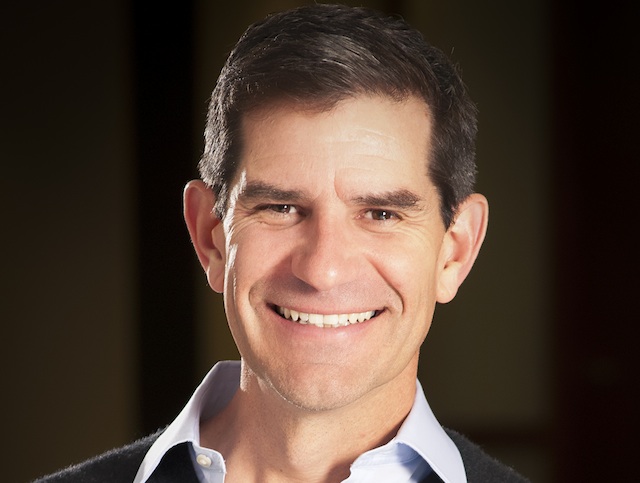

It seems a far jump from running a gaming platform to a remote access software company with a focus on the internet of machines, but that’s the journey remote access company LogMeIn and its CEO Michael Simon has travelled.

“Anything that could be connected will be connected in the next decade.” Micheal told me in Sydney last week and it’s where he sees the next step for the company he has led since its founding in 2003.

LogMeIn grew out of a team that formerly worked for uproar.com, an online gaming company sold to a division of Vivendi Universal for $140 million in 2001.

Two years after the sale Michael, who had been CEO of Uproar, and a team of ten engineers who formerly worked for the company thought they could solve the complexities of accessing computers remotely.

For geeks and big business, accessing your computer across the internet in 2003 wasn’t much a problem however it involved configuring software, punching holes in firewalls and configuring routers.

The LogMeIn team wanted to find a way to make this technology cheap and easy for small businesses and homes to use.

A decade later they employ 650 staff, half of whom are engineers, and have twenty million users of their product.

Building the freemium model

The vast majority of those users are using LogMeIn’s free services – Simon estimates that over 95% of users are using the free version.

In this, LogMeIn is one of the leading examples of the freemium business model – offering a free version of a software product and premium paid for edition with more advanced features.

One leader of the freemium movement was the Zone Alarm firewall, a product which earned its stripes in the early 2000s at the peak of the Windows malware epidemic.

Today one of Zone Alarm’s veterans, Irfan Salim, sits on the LogMeIn board along with two former executives of Symantec, the company whose PC Anywhere and Norton Internet Security products competed with both Zone Alarm and LogMeIn.

While LogMeIn has done well over the last ten years, the market today is very different to that of a decade ago with cloud computing technologies taking much of the need for remote access software

Mike Simon sees these changes as an opportunity with the computer industry having gone through three phases – the PC centric era, the mobile wave and now we’re entering the internet of things.

To cater for the mobile wave LogMeIn has released Cubby, a cloud based storage system that competes with Dropbox, Google Drive and Microsoft’s Skydrive, but Simon has his eye on the next major shift.

Controlling the internet of machines

The internet of things is a crowded market, but Simon believes companies like LogMeIn have an advantage over the telco and networking vendors as businesses with freemium and startup cultures look for ‘pennies per year’ rather than the ‘dollars per device’ larger corporation hope to make.

It’s a big brave call, but with the market promises to be huge – General Electric claimed last year nearly half the global economy or $32.3 trillion in global output can benefit from the Industrial Internet.

That’s a pretty big ticket to clip.

Whether Michael Simon and LogMeIn can achieve their vision of being integral part of the Internet of things remains to be seen, but so far they do have success on their side.

Similar posts: