Has San Francisco become too expensive? An article on Bloomberg business suggests the prices for accommodation and labor have become too high.

Has San Francisco become too expensive? An article on Bloomberg business suggests the prices for accommodation and labor have become too high.

“Of course I’m minimising my tax. If anybody in this country doesn’t minimise their tax they want their head read,” media tycoon Kerry Packer growled when asked about his financial affairs at an Australian Parliamentary committee in 1991.

Kerry Packer’s attitude towards tax minimisation runs deep in the Australian psyche so the announcement of a range of concessions to encourage investment in startups as part of the Federal government’s Innovation Package, branded as The Ideas Boom, may well succeed in unexpected ways.

The National Innovation and Science Agenda should be welcomed by any Australian concerned about the nation’s role in the 21st Century. After 25 years of neglect – if not wilful ignorance – by successive Liberal and Labor governments there is now at least a recognition that developing new industries and businesses is essential to maintain first world living standards.

Many of the proposals in the package are long overdue such as a commitment to open government data, initiatives to support STEM education, programs to encourage women in the IT industry and recommitment of funding for the government scientific agency, the CSIRO.

The defunding of education and CSIRO research by successive Liberal and Labor governments has been one of the quiet tragedies of Australia’s turning its back on the 21st Century. The reversal of the focus on property speculation and mining is hopefully the start of renewed government efforts to restore the long term competitiveness of the country.

While many of us hope this is part of a broader, bipartisan vision of where Australia should be in the connected century, at this stage no-one can have confidence that these long term measures won’t be the victim of short term political expediency.

In the short term however the focus will be on the immigration and investment incentives. In some respects they are disappointing – the $200,000 annual limit for tax benefits should be contrasted with there being no such restrictions on property speculation – and both the investment and immigration proposals are still overly complex and will be a boon for well connected advisors and consultants.

However the changes are a start in shifting the attitudes of the nation’s risk averse investment and business culture and may well be well timed as the real estate price bubble starts to deflate forcing investors and speculators to look elsewhere for returns and tax breaks.

That chase for tax breaks could well mark the change for Australia’s investment starved small business and startup community, at the time Kerry Packer made his comments to the Parliamentary committee one of the most popular tax minimisation strategies was investing in locally made movies under the 10BA scheme that allowed generous deductions for investors.

Most of the films made under the 10BA regime were at best forgettable and the scheme was wound up in the mid 2000s but the wave of money that flowed into the Australian film industry helped launch the careers of many of today’s globally actors, producers and industry professionals.

If these changes can have similar success in the technology industries then they may be well worthwhile.

Another aspect to the Innovation Statement may well be the shift in Australian government industrial policy from a failed ‘think big’ mindset that assumed local businesses had to dominate their domestic markets to compete globally into a view where smaller, nimble operations can succeed internationally.

Overall the Turnbull government’s Innovation Statement is a welcome change from the last twenty years of complacent policy around Australia’s economic development. One big challenge remains though in changing the nation’s complacent business culture.

Ultimately, the biggest challenge is move Australian households and investors on from the tax minimisation mindset. While Kerry Packer may no longer be with us, his mindset remains the driving force of Australian business.

Even before its breathlessly awaited release it appears the Turnbull government’s innovation statement seems to have hit rough water as industry figures and the opposition criticise the proposed requirement for companies to be public before they can raise money through crowdfunding.

In itself this requirement isn’t a major barrier as prominent industry figures have pointed out although it will have the effect of making crowdfunding an option for more established ventures rather than early stage startups, which probably won’t be a bad thing for investors, employees and founders.

The requirement though does show a deeper seated problem in Australian government and regulation – a desire to legislate risk out of the system.

For tech startups, along with other businesses in new industries this creates a paradox as most of them will fail and their investors lose their money. Trying to protect backers of these ventures guarantees they won’t raise money.

So in trying to create a risk free environment, regulators end up killing the ecosystem.

From an Australian perspective, the risk free environment makes sense to a mindset that believes property is guaranteed to double every decade. Why invest in something that will probably fail when borrowing to speculate on an apartment is certain winner?

Strangely that attitude towards property has created another Australian paradox where the real estate industry is exempt from most consumer and investor protection law. The sad truth is the average Aussie has more protection in buying a smartphone case from a two dollar shop than they do when purchasing a two million dollar home.

Because property speculation is seen as risk free, there are few regulations or barriers to Australians gearing up into houses and apartments but for productive businesses and startups the obstacles for raising capital are substantial.

Ultimately, if Malcolm Turnbull and Wyatt Roy want to change the focus of Australian business and investors they are going to have to change the mindset of regulators and voters.

To change that mindset will take some brave steps, for the moment it’s far more likely the budding Australian innovation renaissance is likely to be suffocated by risk hating regulators.

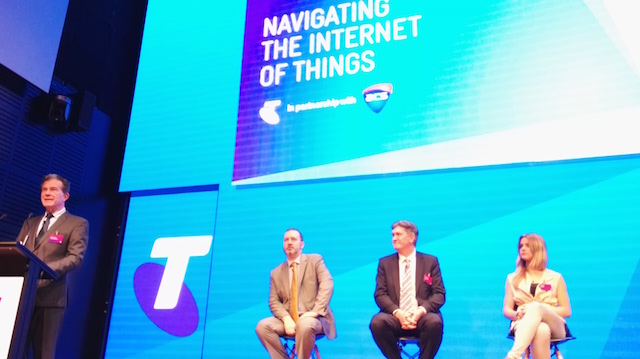

Last week I posted a long interview with Kevin Ashton, the man who coined the ‘Internet of Things’ tag, on startups, innovation and how the media manages to misreport technology. It was a good, but lengthy, interview.

The good folk at Smart Company have rewritten the piece into a much more readable story so if you thought the first post was tl;dr – too long; didn’t read – then you may find the edited version much more concise and useful.

Four years ago group buying sites were the hottest businesses in startup land with the market leader, Groupon, being lauded as the fastest growing company in history and competitor Living Social following close behind it with a $4.5 billion investor valuation at its 2011 peak.

This week the New York Times has a feature on the dire straits Living Social now finds itself in as the company slowly fades away, now only employing 800 people after boasting 4,500 staff at its peak.

Living Social’s big lesson is the risk in chasing customers at all costs. Unfortunately for most of today’s ‘unicorns’ that’s a key part of their growth strategy as an important metric is how many new users are coming on board – the fact a company is making anything from them is largely irrelevant.

While Living Social, and Groupon, are two of the early ‘unicorpses’ – fading or failed billion dollar unicorns – undoubtedly there’s more to come as market realities hit many of today’s chronically overvalued tech startups.