One of the constant questions posed to anyone reporting on the technologies changing the workforce is “where are the jobs coming from?”

A paper by Deloitte UK economists Ian Stewart, Debapratim De and Alex Cole titled Technology and people: The great job-creating machine looks at how technological change has affected the British workforce over the past 170 years.

While the study itself seems somewhat hard to get hold of, The Guardian earlier this week reported on what the economists found when they examined employment patterns through the rapidly changing economy of the last 150 years.

One clear shift the collapse in manual jobs, particularly farm labourers whose numbers fell from a peak of 950,000 in 1881 – 7% of the workforce – to less than 50,000 or 0.02% in 2012.

The decline in the employment of farm labourers shouldn’t be surprising – in 1871 the proportion of the British workforce employed in agriculture was 15% while today it is less than 1%. A graph from the UK Census office illustrates that shift.

It’s notable comparing the UK to the US in this respect; at the beginning of the Twentieth Century nearly half the US workforce was still working in agriculture while the Britain had been a predominantly service economy for nearly fifty years.

Even today nearly 3% of American workers are employed on farms, a number not seen in Britain since the mid 1930s.

In both countries, the late Twentieth Century saw a shift to a service economy, something illustrated in the Deloitte survey by the rise of the British barman where the proportion of workers in the liquor industry tripled from 0.2% of the workforce between 1961 and today.

That British bar employment tripled in the post World War II years probably illustrates best the rise of the consumerist culture during the late 20th Century.

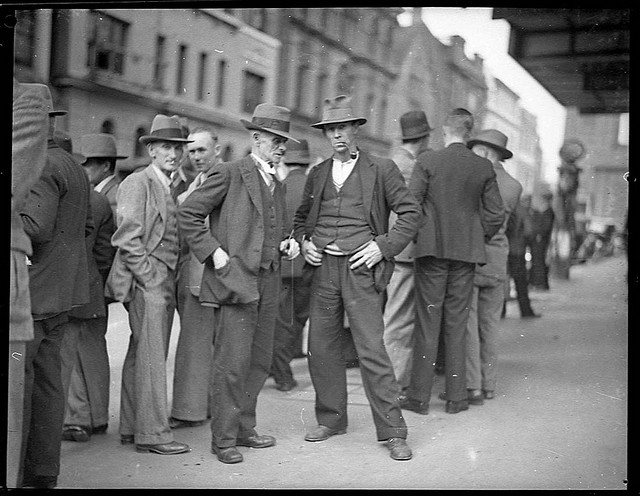

What should be flagged is those transitions away from agriculture to consumerism weren’t painless, much of Britain’s economy was racked by recessions through the Twentieth Century and many of the nation’s regions were devastated by the shift away from manufacturing in the 1970s and 80s.

In the US, the transition away from an agricultural economy in the 1920s was particularly painful, Steinbeck’s book the Grapes of Wrath tells of the human costs to families displaced from their mid-west farms during that time.

That technological and economic factors have driven massive changes over the centuries isn’t new, but the fact the vast majority of today’s workforce are in jobs which couldn’t have been imagined a hundred years ago should encourage us about the prospects for the future workforce.

However, assuming the future will look like today and that employment will be largely in consumer service industries may be as mistaken of the beliefs among 1960s policy makers that manufacturing would be the future.

Even more pressing for today’s policy makers and leaders is to prepare for the pain of transition. If we are seeing a workforce shifting to new business models then there will be high community and personal costs. We need to be preparing for the pain of the shift as much as we anticipate the benefits.

Similar posts: