How can modern computer technology cut the road toll?

Transport for NSW’s John Wall spoke last week at Cisco’s Internet of Everything presentation in Sydney about some of the ways the connected motor car can reduce accidents.

John’s presentation comes from personal experience, having being a volunteer for nearly thirty years at his local State Emergency Service brigade where he was often among the first responders to local vehicle accidents.

Some of the improvements in technology see the road toll falling as people travel less because of remote working, teleconference and business automation. Many of the applications though are built into the vehicles, street signs and the roads themselves.

Finding the safest route

John’s first suggestion for improving driver safety is having navigation systems sourcing traffic, weather and other information to suggest the best route for the driver. An intelligent system may also modify the recommended journey based on the experience of the driver and state of the vehicle, such as the tyre conditions.

Watching the eyes

Fatigue kills and all of us have driven when we were really too tired to be behind the wheel.

The first in car technology John discussed is facial recognition technology that detects when drivers are fatigued. Tying this feature into the vehicle’s entertainment system with a stern aviation style “PULL OVER – YOU ARE TIRED” warning could well save hundreds of lives a year on his own.

Connected road signs

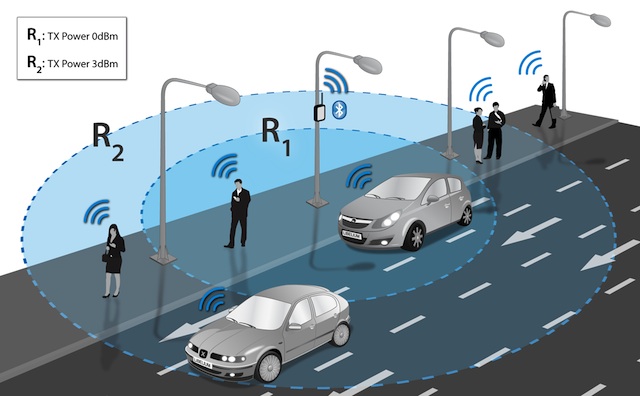

One of the underpinning factors of the internet of everything is cheap computers and transmitters embedded into almost anything. Road signs and sensors talking to cars could help reduce driver errors such as entering curves too fast.

Those signs can also be plugged into weather conditions so if there’s ice, fog or rain then the car can be told of the hazards ahead.

Going on the grid

Signs are not the only devices that could be talking to each other, vehicles themselves could be talking to each other. Should one car hit a slippery or soft patch on the road, it could tell following vehicles that there’s a problem ahead and respond accordingly.

That technology too could help traffic planners and road authorities, as data on traffic speeds and road conditions feed into their databases it becomes easier to identify black spots or road design problems before lives are lost.

Helping the first responders

A wrecked car or roadside sensor can also help those first responders attending an accident. The vehicle itself could transmit the damage and give rescuers valuable, time saving information, on the state of the occupants.

Similarly, the system could also warn emergency services such as hospitals and ambulances of the injuries likely and what’s needed to treat the injuries on site, in transit and at the casualty ward.

Importantly, a smart vehicle can also warn those first responders of potential risks such as live air bag gas cylinders, car body reinforcements or high voltage cables as they attempt to free trapped occupant from a wreck.

The rescuers themselves may be wearing technologies like Google Glass that help them see this information in real time.

Bringing together the technology

As Kate Carruthers points out, the internet of everything is the bringing together of many different technologies – wireless internet, cloud computing, grid networks and embedded devices all come together to create a virtual safety net for drivers.

By the end of this decade that we will all be relying on these technologies to help us drive. Which means we might find our licenses start to be endorsed for the level of technology in our vehicles, just as we used to have to get qualified to drive a car with a manual transmission.

Concluding his presentation, John Wall told the story of Jason, a cyclist from his town who was killed in a road accident and left a young family. In his slide he showed Harry, Jason’s young son, playing with the flowers on his father’s memorial.

“I hope for Harry is that when Harry learns to drive that things will be different on our roads and things will be different because we are all connected,” said John.

It’s a strong reminder of the real human opportunities and costs when we adopt new technologies.

Car crash image courtesy of jazz111 through SXC.HU