Today high rise buildings are the norm on Queensland’s Gold Coast, but just over fifty years ago in Surfers Paradise, nine storey Kinkabool was the first of the breed to be built. Its condition today is a warning on how skyscrapers can turn into expensive liabilities for owners.

ABC Open has an interview with one of the workers on the building and in the accompanying video Bob Nancarrow shows just how Kinkabool dominated the then sleepy seaside resort of Surfers Paradise in 1960.

A visit to Kinkabool today reveals a building struggling in the face of poor maintenance and an undercapitalised ownership. Luckily for the owners’ corporation, the Queensland government pitched in to repair the roof but much of the rest of the complex is showing its age.

The rabbit warren lobby with its orange tiles indicate some of the building was upgraded in the 1970s but apart from a lick of paint, it hasn’t seen much love since.

The lift is are where the building’s age and owners’ lack of investment really shows. An old, slow elevator that hasn’t been upgraded since the first residents moved in clunks its way up the building. Even Hong Kong’s Chunking Mansions – the world’s best example of a dysfunctional high rise – gets its lifts upgraded sometime.

Inside the lift, it’s a depressing scene and one wonders if the antiquated equipment would meet today’s building standards. Even if it does meet the regulations, the dispiriting ride on its own would knock a big chunk off the asking prices for buyers or renters.

Stepping out of the lift, the view in the stairwell isn’t much better. The lack of maintenance or investment begins to show in old fittings, damaged glass and hints of painted over graffiti.

While standing on the ninth floor, music from unit 1B drifts through the building – it’s lucky the occupant has a taste in cheesy 1970s music as some thumping headbanger music could to serious damage to the building along with the residents’ sanity.

One wonders just how noisy the building would be with a party happening or a young, crying baby although it seems families aren’t really interested in these apartments or the central Surfers Paradise location.

Though a very undistinguished building, it does have one touching little architectural feature in the different tile patterns on each floor, although probably not enough to redeem it in the eyes of most people.

Probably the saddest thing about Kinkabool is how a building that once dwarfed everything in the region is now overshadowed by its much bigger neighbours.

Across the road, and blocking out most of Kinkabool’s sunlight, is the 1980s Paradise Centre.

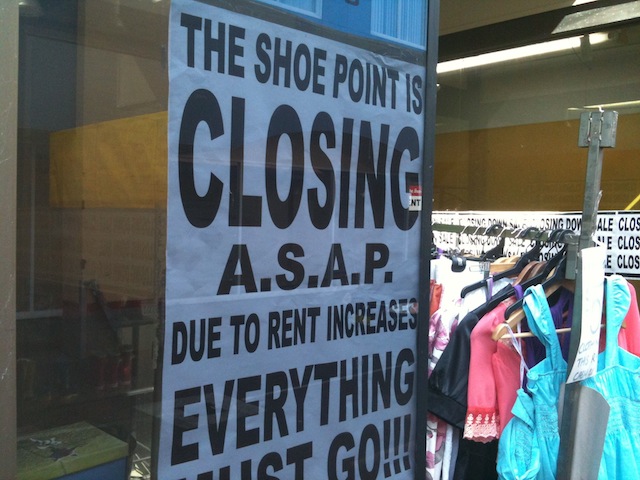

Time isn’t proving any kinder towards the Paradise Centre with the lack of maintenance beginning to show on the thirty-year old complex as this vent across the street from Kinkabool illustrates.

Generally, if the landlord or owners’ corporation is too stingy to afford a coat of paint, then you can be sure there are more nasty surprises

Both the Paradise Centre’s and Kinkabool’s declines illustrate a much more fundamental problem in an economy driven by property speculation and taxation allowances — there isn’t a lot of money to go around for maintaining older buildings.

While Kinkabool’s residents can get by with a clapped out lift, inhabitants of larger and more modern complexes like the Paradise Centre will find the costs of running and maintaining their buildings an increasingly difficult burden.

It could just turn out that Kinkabool, should it escape the wrecker’s ball, may well turn out the more desirable dwelling than its bigger, more modern neighbours.

For the meantime though, Kinkabool marks the beginning of a far more sophisticated era in Australian and Gold Coast history. Whether that era became too sophisticated for itself remains to be seen.

Similar posts:

That the average age of Australian small business owners is increasing shouldn’t be surprising given

That the average age of Australian small business owners is increasing shouldn’t be surprising given